Currently under

construction.

We're adding features,

and making the site

available on phones.

Bear with us...

A few things are working.

Try them out

Currently under

construction.

We're adding features,

and making the site

available on phones.

Bear with us...

A few things are working.

Try them out

Just months into Donald Trump’s second term, it’s clear that his administration is transforming our government. The slashing of health and safety net programs like Medicaid and SNAP will devastate millions of families. The gutting of regulatory oversight will have equally profound and far-reaching effects: Americans will face more exploitation and harm at work, more consumer fraud, more discrimination, and more exposure to tainted food and climate disaster. Even as government is being dismantled in these domains, in other areas the administration is weaponizing the coercive power of the state in terrifying ways. ICE conducts militarized and lawless immigration enforcement raids across the country, while the Department of Justice and other federal agencies target universities, private firms, and civil society organizations that are seen as hostile to Trump, or too committed to progressive causes.

This slew of policy changes is bound by two features. First, they express and help realize a distinctly reactionary vision of American society. This is not just authoritarianism for its own sake—or for the sake of mere corruption, though there has been plenty of that. The goal is to undo, even preclude, efforts at advancing racial, gender, and economic equality, however modest. Second, this vision of a hierarchical social order is being forged through a parallel effort to remake foundational political institutions. Some institutions, from safety net programs to regulations on corporate pollution and malfeasance, have been dismantled, whether through mass firings or defunding. Other institutions, like ICE, have been supercharged. Still other transformations have converted presidential discretion over policies like tariffs or enforcement decisions into tools of personal rule by fiat, based on little more than Trump’s whims. And while Trump has lost the vast majority of legal cases in district courts, his more sophisticated judicial backers have used technical Supreme Court maneuvers and stretched legal theories to fast-track the administration’s remaking of state and society.

These transformations will have a much deeper impact than any one policy. Agencies needed to curb exploitation or protect workers or defend civil rights will be hard to rebuild. And with each breathless headline about a new executive order, the public is increasingly acculturated to believe that rule-by-fiat and authoritarian crackdowns are simply how politics work now. The damage to the very concept of law and governance will be difficult to undo.

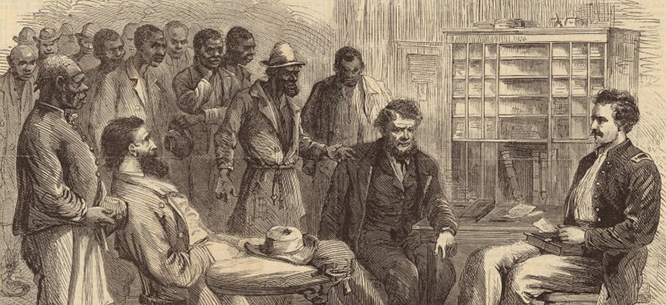

Yet there is another American political tradition that we can draw on in this moment—an emancipatory, democratic tradition that has driven major transformations of our country through bottom-up, movement-driven struggle, often against deeply hostile and institutionalized power structures. Emancipation, abolition, and the First Reconstruction; the New Deal; and the civil rights era all mark moments when social movements and policymakers shifted power away from dominant interests and helped move in the direction of equal dignity and standing for all Americans. While these transformations were imperfect, what is perhaps most remarkable—and most often overlooked—is just how durable some of them have been. As reactionaries attempt to dismantle the achievements of the New Deal and the civil rights movement today, it is important to remember that these transformations occurred in the face of intense opposition from their very beginnings. (Continued)

By Lev Yurkevych & Christopher Ford

Links, Published 29 July, 2025

First published at New Politics. Translation by Terry Liddle. Introduction, editing and notes by Christopher Ford.

Presented below for the first time in the English language is the pamphlet Ukraine and the War by Lev Yurkevych offering what is arguably the earliest concise Marxist analysis of the Ukrainian question to be presented to international socialists.

Yurkevych, a figure whose name and role have been long forgotten in the history of the labor movement, was during his lifetime one of the foremost Ukrainian representatives of the Social Democracy of the Second International. For decades, those who encountered his name — if they did at all — typically did so through the polemics of Vladimir Lenin. In the Soviet Union, where Lenin was venerated as saint without sin, Yurkevych was maligned as a “bourgeois nationalist,” his writings suppressed, and hidden from view.

Yurkevych forms part of a lost left — lost not only through the physical extermination wrought by Stalinist repression and the Nazi occupation of Ukraine but also through a long succession of retrogressive approaches to the history of the revolutionary period which have cast the Ukrainian Marxist tradition pejoratively.

The ideas articulated by Yurkevych and the Ukrainian Social Democrats extend beyond mere historical interest; the challenges they confronted remain profoundly relevant today. In his opening remarks to Ukraine and the War, Yurkevych observed that prior to 1914, European democrats had shown little concern for the Ukrainian question, yet it would play a significant role in shaping the post-war order.

Similarly, prior to Russia’s war against Ukraine commencing in 2014, there was little interest in Ukraine in the West. Since then, interest has markedly increased — a welcome development, but one accompanied by new forms of retrogression.

We have seen a revival of reactionary ideas that Ukrainian Marxists faced in Tsarist times and that were advanced by the White movement during the Civil War. These ideas include that “Great Russia,” “Little Russia” (Ukraine), and Belarus are three branches of a singular Russian people, Russian language and culture being their shared achievement. Moreover, there are the claims that Little Russia is an inseparable part of a unified Russia, and that the notion of a distinct Ukrainian identity is manufactured by foreign powers to weaken Russia.1

Contemporary Russian leaders base their interpretations of the Ukrainian question on these principles in acting as heir and guardian of Tsarist Imperialism. The reburial of General Denikin in 2005 with military honors in Moscow was an apt symbol of this reconnection with Empire. That Denikin secured Western sponsors for his war to reconstruct the Empire is understandable; that Putin can harness support of the far-right is no surprise. What is significant is the support and appeasement of sections of the international left for Russia’s war of colonial reconquest against Ukraine.

In this context the publication of Yurkevych’s analysis holds relevance today. It offers a unique perspective — one that comes directly from a Marxist within the oppressed periphery — on challenges and issues that have resurfaced in our own time.

Lev Yurkevych: A biographical sketch

Lev Yurkevych (1883–1919), who wrote under the pseudonyms L. Rybalka and E. Nicolet, was born in the village of Krivoy — now part of the Zhytomyr region — in what was then Russian-ruled Ukraine. His father, Yosyp Yurkevych was a key figure in the development of the cooperative movement and a leading activist in the Hromada movement that played a crucial role in the Ukrainian revival during the 19th century.

During his university years in Kyiv, Lev Yurkevych was engaged in revolutionary student activism. At the age of 19, he became an active socialist joining the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party (RUP) in 1903 after reading their periodical Selyanyn (Peasant).2

Founded in 1900, the RUP was the first Ukrainian political party within the Russian Empire, playing a crucial role in Ukraine’s political life in the early 20th century. In the lead-up to the 1905 revolution, the RUP experienced significant growth; the paper Iskra noted that RUP leaflets were spread across Ukraine “like snow.”3 In the spring of 1902, Tsarist authorities attributed the mass agrarian strikes to RUP “revolutionary propaganda,” seen by the RUP as the “beginning of the Ukrainian revolution.”4

Initially a coalition of various socialists, radicals, and nationalists, the RUP quickly evolved toward Marxism. By the time Yurkevych joined in 1903, it had formally declared its commitment to the principles of international Social Democracy.

During the years 1904–1905, amid the Russo-Japanese War and revolution, Yurkevych agitated in Kyiv’s factories and streets. Alongside fellow activist Anastasia Grinchenko, they expanded the Kyiv RUP committee, transforming it from a group primarily of intellectuals into one that included active circles of Ukrainian workers.5

This orientation was a major shift from the RUP’s focus on rural Ukraine to organizing urban Ukrainian workers, in an environment where the urban centers saw the primacy of Russians and non-Ukrainian minorities.6 Ukrainians found Russian not only the language of the state but of the labor regime, of the manager and the foreman, with a division of labor that relegated them to the lower strata, with a high proportion of temporary workers being Ukrainian.7 Yurkevych recalled of this campaigning:

Our meetings were mostly about the division of society into classes, the class struggle, socialism, the slogans of the Russian Revolution, current questions, the autonomy of Ukraine and the principle of national organizations. Because of their complexity these last two points were the focus of much attention by our propaganda group. The national character of the work showed in the fact that with Ukrainians we spoke exclusively Ukrainian. At first the workers were a little ashamed to use their native language, but when we spoke it, they always listened with a cheerful smile. It was clear our conversations aroused pleasant memories of their villages, perhaps of their dear ones…. Sometimes we had to defend the right of Ukrainian to exist as a separate language, arguing mainly that the village proletariat constituted the overwhelming majority of the workers, and to ensure the unity of our movement it was necessary to use the majority language; and that the peasantry only understood Ukrainian, and only through this medium would we be able to revolutionize them. And once we’ve done that, we’ll win over the army — the main support of the tsarist regime, which is primarily made up of peasants.8

Yurkevych was to gain some recognition for organizing a strike — not just among ordinary workers, but in the iconostasis workshops, where workers painted icons for the renowned Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra.9 Yurkevych’s success, however, came at a cost, as he faced repeated arrests and imprisonment by the Tsarist police, the Okhrana.10

In December 1905, Yurkevych attended the Second Congress of the RUP in Kyiv, where the party was re-launched as the Ukrainian Social Democratic Workers Party (USDRP). Held on his father’s estate, the congress was nearly cut short when police raided the site on its second day. A few weeks later there were mass arrests, including of Yurkevych, who was incarcerated in Lukyanivka prison. Shortly after his release in May 1906, he was co-opted into the USDRP Central Committee; then after another prison term, Yurkevych, aided by smugglers, fled the Russian Empire in 1907, though he returned several times illegally.

Despite his exile, Yurkevych remained a pivotal figure in Ukrainian Social Democracy, serving as both an organizer and theorist. His efforts in coordinating and funding party publications were crucial to the survival of the USDRP.

At this time, Ukraine was divided between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires, with Ukrainian Social Democracy forming distinct parties in each region. In 1899, the Ukrainian Social-Democratic Party (USDP) was founded in Galicia, an autonomous party within the federal All-Austrian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party. In 1913, Yurkevych briefly served as the secretary of the USDP in Galicia.11

In the years leading up to the 1917 Revolution, Ukrainian Social Democracy emerged as the most consistent and prolific force in political publishing in the Ukrainian language. The USDRP published more than twenty newspapers and periodicals and republished works by key socialist leaders of the period. Their materials had a significant influence, extending well beyond their own ranks.

The work of Ukrainian Social Democracy was historically significant in seeking to move the Ukrainian movement beyond solely cultural concerns of russification, to see the anti-colonial struggle as simultaneously a social question.12 The Ukrainian Marxists were represented in both the Tsarist Duma and the Austrian Reichsrat and were active at an international level, submitting regular reports to the congresses of the Second International.13 Yurkevych himself attended the International Socialist Congresses in Stuttgart in 1907 and Copenhagen in 1910.

Yurkevych, Mykola Porsh, Volodymyr Levinsky, Yulian Bachynsky, and Mykola Hankevych were among those involved in controversies with such figures as Otto Bauer, Georgi Plekhanov, and Lenin over the national question. Yurkevych addressed the Congress of the Czechoslovakian Social Democratic Party in December 1911, expressing solidarity with Ukrainian and Czech autonomists whom he defended as internationalists.14

In the years before the First World War Yurkevych played a key role organizing various USDRP publications. One of the most notable was Dzvin (The Bell), which brought together a diverse range of contributors, including figures from different wings of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (RSDRP). The journal also served as a platform for debates on the national question — notably, between Yurkevych and Lenin.

Writing in Nash Holos (Our Voice) Yurkevych summarized his views on the USDRP and the national question:

The root of the issue lies in the attitude of national passivity of the social democracy. Rejecting that view I decided to argue in our press along the following lines: 1) national consciousness is indissolubly linked with class interests and class consciousness. This constitutes a new form of the expression of the class struggle. 2) The proletariat has no fatherland, but it cannot lack a nationality that it shares with the other classes of its people. It is therefore interested in the freedom and development of national life. This commonality is formal; but the national consciousness and politics of the socialist proletariat cannot be separated from its class interests, nor can they be equated with the national consciousness and politics of other classes. 3) The social-democracy of nationally oppressed peoples must work on developing the national-class consciousness of the working class in the interests of (a) its own development and its transformation from an exclusively rural organization into a general workers’ organization of its nation (b) the clear demarcation of the proletariat within the national sphere through the speech and activity of the organization and its party (c) the intention to speed up and widen the revolutionary struggle of the proletariat for national freedom.15

The Ukrainian Social Democrats’ views on the national question, their policy of national autonomy, the subjective forces of the revolution, and the nature of the post-revolutionary order marked a point of demarcation with the Russian Marxists.16 The RSDRP demanded the subordination of all Marxists in the Empire to a single party — their own. As a corollary Lenin supported the assimilation of workers into the Russian nation as historically progressive and refused to challenge the integrity of the Russian Empire.17 In contrast the Ukrainian Marxists took up the national question as a task of the immediate, minimum program of Social Democracy, considering that the advent of socialism would promote a springtime of nations and national culture.

There was, wrote Yurkevych, a progressive side to the national revivals, “a creative and cultural energy displayed by separate classes according to their specific social interests.”18 But the Marxists of the dominant nation were blinkered, they only saw negative attributes “in the national movements of oppressed nations, as a capitalist sees the expansion of the rebellious spirit as the result of the activity of some secret agitators, hostile towards him, in the workers movements.”19

We demand one thing, namely: we, the Marxists of an oppressed nation, must have the opportunity to freely and independently carry out our social and national activity.

This demand seems to be very modest and fully corresponding to a nation’s right for self-determination, recognized by all Marxists.

However, this right is refused to us in practice, because they do not allow us to establish organizations adapted to our national and political objectives.20

Experience proved the necessity of federative forms in the international unification of workers.

The principle of federalism that we, the Ukrainian Marxists, are upholding as a basis for our unification with the Great Russian Marxists, in our opinion ensues from the entire history of the world labor International.21

This was reinforced, argued Yurkevych, by the experience of the First and the Second Internationals, which operated on federalist principles.22 In one of Yurkevych’s responses to Lenin entitled Jesuit Politics, he noted that the “Russian Marxists had a contemptuous and sometimes even hostile attitudes towards us, Ukrainian Marxists, only because we attach great importance to the national question and conduct our activity in national forms.”23 Yurkevych acknowledged the RSDRP had moved from indifference and was now divided, with a minority “trying to understand the nature of national workers’ movements in exploited nations.” Whilst the majority “with uncommon fanaticism and sectarian obstinacy promulgates old centralist ideas and absolute intolerance towards the national self-organization of workers.”24

As the First World War loomed, Yurkevych — like most USDRP leaders — maintained a firm anti-war stance. At the 1912 International Socialist Congress in Basel, the USDRP and USDP submitted a joint appeal. “Raising our voice against the war, against Russian imperialism and its scoundrel policy, …we call upon the entire Socialist International to raise its cry of protest against the unheard-of criminal policy of the Russian tsardom, which is preparing national death for a numerous people.”25

Ukrainians found themselves on opposing sides, three million from the Russian Empire, later along with Ukrainian immigrants in North America, fought for the Entente, while 250,000 from Galicia, Bukovyna, and Transcarpathia served Austro-Hungary. Both sides persecuted Ukrainians. The Russian Imperial government swiftly arrested Ukrainian leaders and suppressed newspapers. Within a month, Russian forces occupied Galicia, launching anti-Ukrainian measures, including arrests, book burnings, the abolition of Ukrainian education, and forced conversions to Russian Orthodoxy. Concurrently, the Austro-Hungarian army interned 30,000, alleging pro-Russian sympathies. In Canada, thousands of Ukrainian immigrants were similarly interned, accused of pro-Austrian loyalties.26

Within Ukrainian Social Democracy, opposition to the war and support for a Russian “defeat” were widespread.27 Only a small minority of leading figures adopted a pro-Russian or pro-Austrian orientation, as seen in the USDP in Galicia, while a handful of figures from the USDRP joined the Austrian-sponsored Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU).28

Yurkevych, along with the USDP leader Levinsky travelled to Vienna, and there tried to publish an anti-war statement in the leading Social Democrat paper Arbeiter Zeitung. The editor, Austerlitz, threatened them with arrest. Under surveillance in Vienna, Yurkevych took refuge in Geneva. Under Yurkevych’s editorship, the newspaper Borotba was launched in Geneva as the official organ of the “Foreign Organization of the USDRP,” enrolling the support of various exiled USDRP members across Europe.

Declaring complete solidarity with the anti-war Zimmerwald movement, Borotba stated: “Above all, we should not take sides, not besmirch our revolutionary cause in showing solidarity with the war aims of any of the governments involved.”29 Over the next two years Borotba subjected the Russian and Austrian orientations to relentless criticism, whilst exposing the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine as a “lackey of that [Austrian] government,” engaged in “the profitable role of the Emperor’s own revolutionists.”30

At the second anti-war Conference, in Keinthal on 23rd April 1916, Yurkevych submitted an Open Letter in French, Ukraine and the War.31 In a prognosis to be confirmed at the treaty of Brest Litovsk in 1918, Yurkevych condemned Ukrainian politicians of an Austrian orientation. He warned “they have lit the torches of Ukrainian independence — to light up the route of the Austrian armies towards Kyiv”; as opposed to emancipation, they “seek to light the fire of German capitalist exploitation in Ukraine in order to warm themselves by it.”32 Yurkevych warned against illusions in the democratic credentials of the Russian bourgeoisie which would continue the policies of imperialist expansion and Russification. Yurkevych joined in the call for a new international, appealing:

Just as the first International and all European democrats were committed to the liberation of Poland from the yoke of Russian autocracy, we are sure that the liberation of Ukraine will be the watchword of the third International and of the proletarian socialists of Europe in their struggle against Russian imperialism.33

Yurkevych endorsed the Keinthal policy on the national question as being in accordance with the USDRP “principle of national autonomy,” which “will be a great support to us in our activities and against those who, consciously or not are always trying to blacken us questioning our socialist credentials.”34

Yurkevych faced ongoing efforts to discredit Borotba from elements within both Ukrainian and Russian Social Democracy. In response to Ukraine and the war, the USDP in Galicia had issued a letter to various socialist parties, expressing astonishment at his views. They argued that due to the “complete atomism of Ukrainian Social Democracy in Russia,” Yurkevych was acting alone and, by opposing an “independent Ukraine” was “serving Tsarism but not social-democracy or the Ukrainian people.”35

This criticism was not unprecedented. In an open letter the previous year, Dyatlov — a member of the USDRP Central Committee — rejected such claims. He argued that the assertion “that the views of Borotba are the personal views of ‘Mr. Rybalka’ [Yurkevych] does not correspond to reality,” and affirmed that “the views of Borotba truly reflect the traditions of the USDRP.”36

Most prominent in the efforts by Russian Social Democracy to discredit Yurkevych and the USDRP was Sotsial-Demokrat,the exiled paper of Lenin’s faction, which had initially expressed approval of their views on the war.37 Yurkevych developed amicable relations with other currents of the RSDRP, including the Vpered group and Leon Trotsky’s Nashe Slovo. The Foreign Group of the USDRP had solidarized with the Bolsheviks, declaring:

We agree with the Bolsheviks that the defeat of Tsarism in this war will contribute to the weakening of the old Russian State system and make easier the tasks of the coming Russian revolution…. Furthermore, we connect with the Bolsheviks in their decisive fight against social patriotism.38

Despite repeated efforts by the USDRP, the Bolsheviks were unable to reconcile their differences with them regarding the national question and party organization. Yurkevych met with Lenin in Geneva and was perplexed by his unsympathetic attitude toward Borotba. Reflecting on this in July 1915, he confided to Leon Trotsky, “Why? I have no idea.” Trotsky was also puzzled replying, “I have to say that I like your Ukrainian articles which you have sent for Nashe Slovo.” Indeed, Trotsky expressed disagreement with Yurkevych’s views on the revolutionary potential of the defeat of Russia precisely “because this position brings you together with the followers of Lenin. At first glance the hostile attitude of Lenin towards your periodical seems absolutely inexplicable to me.”39

Independence and dependence

A key point of contention was the question of Ukrainian independence in the context of the war. Yurkevych distrusted Lenin’s framing of national self-determination as a binary choice: either a centralized union with Russia or outright separation — despite Lenin’s opposition to the latter. Writing in Borotba on the significance of the second international socialist conference, Yurkevych reflected critically on this question:

We are not opposed to the idea of an independent Ukraine but the question of our state independence can only be decided when the chains of Tsardom and Russian state centralism are destroyed. When Ukraine is reborn and has reached the level of civic consciousness found for example in Ireland. When the Ukrainian democracy understands the entire awful reaction that goes under the name of the Russian Empire. But now, while even the printed word in Ukrainian is forbidden, while Ukraine is deprived of the smallest civil freedoms and subjected to limitless Russification the only way out for the Ukrainian democracy is a joint struggle with the working masses of Russia against all the black Tsarist and imperialist forces.

Our Russian comrades will only show themselves to be true internationalists when their organization and press in Ukraine recognizes along with us the need for the struggle for the liberation of our people, and on every occasion along with us in resisting in a revolutionary way any manifestations of national oppression.40

Indeed it was from the Irish struggle that Yurkevych took inspiration. Following the Easter Rising of 1916 he wrote in Borotba:

The only enslaved nation that has preserved its dignity amidst the general confusion of nations in times of modern war is the Irish, who organized a courageous uprising at the most critical moment for their oppressor — England.41

Contrasting the situation of the Ukrainian movement in July 1916 to Ireland, Yurkevych looked to a time when “Our working class will not be an exception; it will choose for itself new and more honest leaders, inflamed with hatred of slavery and distinguishing itself among the Ukrainian people against all those that are in a close and sincere relationship with the Russian state.”

Lenin continued his polemics against Yurkevych with all their inaccuracy and invective, when Sotsial-Demokrata published a Sbornik (anthology) on the national question in October 1916. Though it did not name Lenin as the author, it published his text The Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination. In January 1917, Yurkevych responded with a comprehensive critique: The Russian Social Democrats and the National Question.42

Yurkevych argued that by holding to two mutually exclusive propositions, the “right of nations to self-determination” with a preference for large states and centralism, it “destroys within them the capacity to consider the national question from a genuinely internationalist point of view.”43

With this in mind and as if to confuse the issue once and for all, the authors of the “theses” note that in actual fact, “the demand for free secession from the oppressor nation” “is not at all equivalent to a demand for secession, fragmentation, or the creation of small states.” It follows from this that the program of the central organ of the RSDRP on the national question, consisting in the recognition of “the right of nations to self-determination” and in its simultaneous denial — equals zero.44

Yurkevych’s analysis was dialectical: “the capitalist order, while oppressing nations, simultaneously regenerates and organizes them.” It was as such “impossible not to agree with Bauer that nations will fully develop only under socialism,” with “social progress by means of its peaceful diversity.”45 Yurkevych also saw problems in Lenin’s prognosis with regard to the achievement of bourgeois democracy in Russia, instead “considering the reactionary and blatantly imperialist character of the policies of the Russian bourgeoisie, one can say with certainty that it will not only not oppose the weakening of Tsarist centralism, but will strengthen it.”46

This assessment by Yurkevych was largely vindicated when Kerensky’s ultra-democratic republic resisted Ukraine’s quest for national autonomy between March and November 1917. The difficulties of the revolutionary process in Ukraine from 1917 to 1921 saw another of Yurkevych’s prognoses arise with tragic consequences.

Posing the question how the Russian workers would respond to a Ukrainian rebellion, Yurkevych contended that Lenin had, for over a decade, educated them to favor a centralized state and oppose “the break-up of Russia,” creating the possibility that if “the Ukrainian workers, believing in the ‘right to self-determination,’ join the rebellion, the Russian proletariat will call them traitors,” and go to war against them in the name of “emancipation.”47

This conflict between the internal forces of Ukraine and external elements of Russia, was to hinder the Ukrainian Revolution’s development, and obstructed the consolidation of a Ukrainian republic shaped by internal social forces.

Thus, in December 1917 — on the very day the All-Ukrainian Congress of Workers, Soldiers, and Peasants gave its full support to the Ukrainian People’s Republic — the Bolshevik government of Russia launched a war against Ukraine, whose government was a socialist coalition led by the USDRP.48

In 1919, a second Bolshevik government was imposed on Ukraine, that provoked a mass rebellion of whole sections of the Red Army and red militia. The uprising was led by a pro-Soviet fraction of the USDRP — the Nezalezhnyky (Independents) — who called for the independence of Ukraine with a government of the working people.

When the Nezalezhnyky founded the Ukrainian Communist Party, they condemned the fact that “under such conditions, the socialist revolution in Ukraine in both cases took the shape of an occupation by Soviet Russia.” The Bolshevik leaders were “separated from the working masses of Ukraine, who turned against them.” It was imperative, they argued, for internal forces to “gain control over the Ukrainian socialist revolution and shape its course and character.”49

The legacy of Yurkevych

The Russian Social Democrats and the National Question was Yurkevych’s final publication. After the February Revolution he attempted to return to Ukraine via Finland and disappeared for a time. His sister, living in Moscow, eventually found him in a Finnish prison hospital, nearly unconscious due to psychosis following typhus.

Upon his return to Moscow, despite his fragile health, Yurkevych was immediately arrested and imprisoned. Rescued by his family at the end of 1918, he remained largely unconscious until his death on October 24, 1919. Buried at Novodevichy Cemetery, he never returned home — his memory eclipsed by subsequent events. It was not until 1927 that even an obituary appeared, published as a pamphlet by Levynsky by the Ukrainian Socialist Library in Lviv.

Although a lost leader of the Ukrainian Revolution, Yurkevych made a significant and largely unrecognized contribution to the rebirth of Ukraine between 1917 and 1920. Yurkevych’s contribution was twofold: first, during the years of reaction following the defeat of the 1905 Revolution; and second during the First World War.

The strong stance taken by Yurkevych and Borotba resonated in the USDRP revival that began soon after the start of the war in 1914. Yurkevych had re-established contact with leading activists of USDRP inside the Russian Empire already in late 1914.50 Vynnychenko wrote to Yurkevych in December 1915 stating “we all stand on your side… the word revolution is on everyone’s lips.”51 The strongest wartime organization of the USDRP was in Petrograd, which had a sizable Ukrainian community and a garrison with many Ukrainian soldiers. Between 1915 and 1917, the local committee published the paper Nashe Zhyttya (Our Life). On the issue of the war the Petrograd organization stood with the positions of Borotba, edited by Yurkevych. It republished Borotba’s declarations and articles, which were circulated beyond the city and into Ukraine itself.

The USDRP had launched a newspaper Slovo in Kharkiv in October 1915.52 In the city of Katernynoslav (Dnipro) the USDRP continued to operate and conducted anti-war propaganda. A conference was held there in November 1915, rejecting the position of the Union for Liberation of Ukraine and arguing to focus on preparing Ukraine’s own forces for a revolution against Tsarism.53 This view was strengthened by the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland — which found a lively response among the USDRP, as proving “that a national liberation struggle against ‘one’s’ metropolis was possible without a general revolution in the entire country, which strengthened the position of supporters of a general national struggle against Russia.”54 The Kyiv organization of the USDRP also reorganized, calling “for a fight, not with the Germans, but with our oppressors — the government and the nobility.”55

When the February Revolution of 1917 brought the downfall of the Tsarist regime, at the same time it played a significant role in the All-Russian revolution: the intervention of the Izmailovsky and Semenivsky regiments decided the fate of the revolution, whose soldiers were organized by the USDRP.56

With the overthrow of the autocracy, the Ukrainian Revolution soon differentiated itself from the wider Russian Revolution, setting as its goal the achievement of national emancipation through establishing a Ukrainian Republic. It was a period of unprecedented mobilization of the masses. The movement comprised a bloc of the middle class, peasantry, workers, and democratic intellectuals, centered in the Ukrainian Central Rada [Council]. Its very existence was an historic achievement; transforming a situation from one where officially Ukraine did not even exist, to one by July 1917 where the hostile Russian Provisional Government was forced to recognize it as a “higher organ for conducting Ukrainian national affairs.”57 In historical terms it represented for Ukraine what the Easter Rising and First Dáil did for the Irish Republic.

The USDRP was pivotal to this achievement. As the only political party in the strict sense of the word, it already had trained activists and organizers, and its name — as well as those of its leading figures — was known among broad circles of Ukrainian workers. As a result, the USDRP was able to assume a leading role in the revolution and in the first Ukrainian government of 1917–18, headed by Vynnychenko.58

Yurkevych sought to bring the working class to the forefront of the Ukrainian struggle. In Ukraine and the War, he considers the role of the Ukrainian socialist movement as significant in the “national renaissance,” connecting the “the question of national emancipation to all the problems of the emancipation of the proletariat.” From this perspective, his efforts during the years of reaction after 1905 proved crucial to ensuring the survival of the USDRP.

Through his defense of Ukrainian self-organization, his organizing of numerous publications, and his efforts to sustain the USDRP, Yurkevych played a pivotal role in enabling the party to survive — and ultimately to assume its leading role in Ukraine’s rebirth.

That rebirth of Ukraine — achieved despite all the horrors endured by its people has never been reversed, until now, as Russia once again plays the role of a gendarme of Europe, whose program is to absorb Ukraine and subjugate other nations. It is a timely moment to rediscover the neglected figure of Yurkevych who anticipated many of the challenges and devoted such attention to these problems we face again today.

Christopher Ford is Secretary of the Ukraine Solidarity Campaign in the UK, and is author of a range of books and articles on Ukrainian labor history, including editor of Ivan Maistrenko, Borotbism: A Chapter in the History of the Ukrainian Revolution and Ukapisme – Une Gauche perdue: Le marxisme anti-colonial dans la révolution ukrainienne 1917 – 1925. He has a forthcoming book of selected writings of Ukrainian Social-Democracy.

Ukraine and the war: An open letter by Lev Yurkevych

Addressed to the Second International Socialist Conference, held in Holland, by the editors of the journal Borotba (The Struggle) and published in Geneva by a group of members of the Ukrainian Social-Democratic Workers Party of Russia.59

Comrades,

The Ukrainian question is one of the national questions which up to the present time European democrats have shown very little interest in. However, in recent years, after the Russian Revolution and above all during the present World War, this question has started to play a considerable role in the internal life of Russia and Austria — and without doubt will put itself on the order of the day when Europe addresses itself to finishing this present war.

That is why, comrades, our Ukrainian democratic socialist group in Russia says that it is its duty to explain before you, albeit briefly, the Ukrainian question in the hope that you will take note of our considerations in the debates and decisions taken by this conference.

IThe history of Ukraine is far from happy. The Ukrainian lands were on the route of Asiatic peoples moving toward the West. For long periods this prevented Ukraine from enjoying a tranquil life and from organizing itself freely, which let it fall under the domination of neighboring states. Thus it became part of the Lithuanian state up to the sixteenth century, and then when Lithuania was united with Poland it was annexed by the latter. Polish domination placed a heavy burden on the Ukrainian people and led Ukraine, which during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries had increased its territory and organized itself militarily, to revolt during the middle of the seventeenth century, and, after a long war of liberation led by the Cossacks, to separate from Poland and form an independent Cossack republic.60 Yet circumstances obliged Ukraine — menaced by its neighboring Turkish and Polish neighbors — to seek an ally. It found this ally in the Muscovite state, which it was tied to by a common religion but which differed from it through its ferocious despotism and extreme centralist politics.

The Union was made in 1654 and Ukraine allied itself to Moscow as a free and independent state, having its own army. Despite this convention, Moscow sought immediately to curtail the freedom of Ukraine and signed an accord with Poland, giving it western Ukraine (the right bank of the Dnieper) — which had just freed itself from Polish domination. The popular uprisings in eastern Ukraine (the left bank of the Dnieper) against the despotism of Moscow were put down by Muscovite force. After a fifty-year struggle, ended by the famous “treason” of the Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa who allied himself with Sweden and was defeated by the army of Tsar Peter the Great, one of the last blows struck against Ukrainian independence by the destruction of the autonomous Cossack military organization. Toward the end of the eighteenth century the last vestiges of its political independence were destroyed. After the partition of Poland, eastern Ukraine was annexed by Russia with the exception of Galicia, which went to Austria; Ukraine was divided into governments [gubernia] and then crushed by Russian bureaucracy.

Ukrainian culture, which had undergone considerable development in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in parallel with Polish culture and under the influence of Western civilization and the Reformation, was destroyed by the despotic Muscovite state. The Ukrainian nobility which during the struggles against Polish domination had shown so much energy and love of liberty did not resist Russian centralism and finally submitted in exchange for hereditary noble titles and landed wealth. The popular masses reacted against this treason by the ruling classes to the cause of Ukrainian freedom by a series of cruel and bloody rebellions known under the name of “Haidamachchyna.” This long series of popular social movements was suppressed in the last years of the eighteenth century by the Russian Empire, which introduced serfdom in Ukraine thus condemning them to silence for many years.61

During the end of the eighteenth and the first part of the nineteenth centuries, Ukraine — crushed by the heavy domination of the Russian bureaucracy [and] deprived completely of its past liberties — submitted, resigned to its fate. Yet during the early nineteenth century the libertarian ideas of philosophy and of the French Revolution penetrated Ukraine, where they took a democratic and Slavophile form adorned with romantic Cossack traditions. Eastern Ukraine in particular produced a number of writers who had concerned themselves with history and ethnography and who bequeathed a great number of scientific works.

But the Ukrainian movement didn’t really appear until the so-called liberal era around the 1860s, marked by the emancipation of the serfs and a whole series of social reforms. While Poland was shaken by insurrectionary ideas, libertarian tendencies manifested themselves differently in Ukraine. The Ukrainian ruling classes, who under Polish domination were strongly influenced by its culture and had not successfully created a culture for themselves after liberation from Polish rule, Russified themselves rapidly after the annexation of Ukraine, so that by the middle of the nineteenth century these classes were separated from the people by an insurmountable barrier formed by a culture alien to the people so could not concern themselves with questions of national interest. As a consequence, the Ukrainian intellectuals of this period, who could not take their ideas to the upper classes, took on ideas of a democratic nature. Their nationalism, exempt from separatist and insurrectionist ideas, expressed itself above all in their desire to free the serfs, to raise their national consciousness, and to unite them.

Amongst the Ukrainian people the national revolutionary tendencies of the nobility had long since vanished, therefore the Ukrainian renaissance of the second part of the nineteenth century took the form of a bourgeois movement. The romantic Cossack traditions were no more than yesterday’s “leftovers,” which however held it back from total embourgeoizement and taking this position vis-à-vis the Russian Empire and its regime.

Whereas with other oppressed peoples such as the Czechs, or the Ukrainians of Austria, the transition of national development went from the insurrectional form of the old nobility to the modern bourgeois democratic form coinciding with the democratization of the ruling state, this was not the case with the Ukrainian awakening in Russia. There this awakening to a bourgeois and democratic form was born under an absolutist regime and remained there for a half century until the Russian Revolution.

This fact gave the Ukrainian renaissance in Russia an extraordinarily passive and powerless character, as for a long period it lacked a free constitutional regime, something absolutely indispensable to any modern bourgeois and national movement.

This is why the Ukrainian movement manifested itself so weakly. It was behind in its development compared to the subject peoples of Austria, who long enjoyed their political liberty; the path to this was closed by despotic Russian centralism.

Russian Tsarism was always hostile to the Ukrainian movement and in its struggle against this movement resorted to the most severe means of repression. This can be explained by the role Ukraine played in the foundation of the Russian Empire. The Muscovite state could not transform itself into the Russian Empire until it had annexed Ukraine, from which it took the old name “Rus.”62 It was not until after it had seized the black earth belt of Ukraine and the banks of the Black Sea that the Muscovite state, which occupied the northern part of Russia proper and which did not possess large natural resources, could take part in world economic life and become the Russian Empire. The Muscovite despotism which knew so well how to exploit Ukraine and disorganize its people, leading an intense and harsh life, knew how to Russify the Ukrainian ruling classes so that finally the Muscovite state succeeded in its official policy: to treat the Ukrainian people as one with the Russian people.

The Ukrainian nation formed with the Russians an overwhelming majority in Russia, which was a prop to the grandeur of Tsarism and Russian imperialism. But if the Ukrainian nationality came back to life, shaking off Russian bondage and forming an independent entity, the Russian nationality would be a minority of 43 percent in the Empire. It is understandable that Russian Tsarism was frightened of such a perspective, hence it constantly displayed total and thorough opposition to all Ukrainian movements.

We have already said that the modern Ukrainian movement started to develop around 1860. It manifested itself at this time by the pacific desire to organize popular Ukrainian education. At this time Sunday schools were founded in different Ukrainian towns, particularly in Kyiv, its capital. Education was conducted mainly by high school students, who at the same time published textbooks for the people in their mother tongue. But Tsarism struck immediately against this inoffensive manifestation of the Ukrainian movement. In 1863 publication of Ukrainian literary works aimed at the people were banned and the minister Count Petr Valuev declared “the Ukrainian language doesn’t exist, has never existed and never will exist”! The following year the Sunday schools were closed. This persecution greatly discouraged and weakened the young Ukrainian movement. But the Tsarist government didn’t stop there. On the eve of the war against Turkey in 1876 — undertaken under the name of “liberation of the Bulgarians” — a decree banned all Ukrainian-language publications.63

After this decree, the Ukrainian movement was deprived of printed matter and found it totally impossible to legally display its existence until the revolution; this was for a whole thirty-year period. Strange to say, this savage attack on Ukraine did not provoke any reaction on the part of Ukrainian leaders.

Despite the passive nature of the Ukrainian movement, the intellectuals of 1860 were infused with determined political ideals, the best known representative of which was the “Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood” founded in 1840. This association counted amongst its leaders the poet Shevchenko, the writer Kulich, and the celebrated historian Kostomarov. The Brotherhood, the aim of which was the abolition of serfdom, had a Slavophile character. This differed from Russian Slavophilism, which was always imbued with a centralizing pan-Russianism and advocated a Slav federation of which a free Ukraine would be part.

The Russian government quickly discovered the existence of this Brotherhood and persecuted Shevchenko, who was exiled to Siberia for many years and forbidden to write; Kulich and Kostomarov were forbidden to live in Ukraine. But their ideas did not perish; they animated the Ukrainian patriots of 1860, particularly the youth involved in popular education. Yet these ideas were not at all revolutionary and faced with repression, particularly the 1876 law, the Ukrainian leaders renounced their political ideal, capitulating to Tsarism all along the line.

The most powerful of the leaders of the Ukrainian movement of 1860, M. Drahomanov, a professor at Kyiv University, emigrated to Switzerland, dedicating his life to the idea of Ukrainian liberation.64

In vain he exhorted his countrymen to struggle against Tsarism, to publish Ukrainian revolutionary papers in free Galicia, to be distributed throughout Russian Ukraine; his appeals were not heeded. The Ukrainian leadership within Russia would do nothing but submit to the censorship of Ukrainian manuscripts, which the government time and again refused permission to print. The watchword was “Conciliate the government.” The recognized Ukrainian leaders sent reports to St. Petersburg, asking the government’s permission to engage in popular education, with the assurance that this concession would weaken the revolutionary elements within the Ukrainian movement, which would retain an exclusively legal character. They also expressed the view that political struggle should be left to the Russians in Russia and that the Ukrainians should limit themselves to popular education and remain strangers to all politics.

Despite the humility of bourgeois Ukrainians, Tsarism continued to persecute with a cold and intransigent perseverance any manifestation of Ukrainian nationality, however inoffensive; at concerts singers were obliged to sing Ukrainian songs in French translation.

Thus the bourgeois Ukrainian movement, aspiring to a liberal constitutional regime with a view to organizing a reborn nation, was placed by circumstance in a position where all activity and all political initiative were without result. This bourgeois movement separated itself from the masses and was reduced to ultra-anodyne displays; one such was an edition of a journal published in Kyiv in Russian and dedicated to the Ukrainian past when theatrical representatives enjoyed a little liberty at the end of 1880.

The bourgeois Ukrainian movement distinguished itself in this case and to the highest degree by a trait common to all the modern bourgeois movements of oppressed nations. These movements could not adopt any of the proper characteristics of the bourgeois revolutions of Western Europe. Representing the interests of the middle classes at their beginning, the bourgeois movements of the oppressed nations had a policy without principle, a policy of compromise with the existing states which, ultimately, were a factor which ensured the capitalist development of oppressed nations, for the centralism of the great empires could retard the development of any nation but not ultimately stop it.

The revolution of 1905 was the force that obliged Ukraine to emerge from its inaction. The period before the revolution in the first years of the century performed a great role. Since the end of the last decade of the nineteenth century the workers’ strike movement sparked among Ukrainian scholars a growth in hope. This growth, created on the one hand by Russian socialist literature and on the other by the revolutionary works of Drahomanov, caused the youth to indignantly condemn the old tactics of the leaders of the Ukrainian movement. At the university of Kharkiv, where the historical and ethnographic studies of the professors had been the base in the last century of the Ukrainian movement of 1860, there formed at the start of the twentieth century, this time among students, an energetic group of revolutionary and socialist Ukrainians who in 1900 founded the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party, the appearance of which was the starting point of a new period for the Ukrainian movement.

This party broke completely with all the traditions of the old leaders of the Ukrainian movement. It initiated its activity directly amongst the people, making use of an abundant literature published in Austrian Ukraine. This literature smuggled into Russia in dozens of kilos spread very rapidly throughout Ukraine. These journals and pamphlets excited the interest of the toiling masses and were received by them enthusiastically, happy to get the socialist truth in works published for the first time in their muzhik tongue; the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party [RUP] was the first to infringe clearly and openly the decree of 1876 banning Ukrainian publications.65

Although by its activity amongst the peasants the RUP broke with the traditions of the Russian social-democrats, who at this time were not interested in the toilers in the countryside but only industrial workers, it did not follow the tactics of the Narodniki, and constantly gave to its propaganda a class character addressing itself to the peasants and organized their strike movement.66 In this area the RUP had considerable success and it was due in great measure to them that the strike movement in the gubernias of Poltava and Kharkiv became one of the forerunners of the revolution in Russia.

The Revolutionary Ukrainian Party was a socialist party. But it was not so in theory or in its program, though on the eve of the revolution its activity also took place amongst urban workers. A second constitutional congress of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party took place in 1905 and adopted the maximum Erfurt program of the German Social-Democrats and the minimum program of the Russian Social-Democracy. It demanded extreme democratic autonomy for the territory within the ethnographic boundaries of Ukraine, with legal guarantees for the free development for the national minorities living within its territory. The principle of national organization was based on the organizational model of the Austrian Social-Democracy.67

With regard to tactics, the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party took the same position as the left wing of the Russian Social-Democracy (Bolsheviks), and instead of calling itself the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party, adopted the name Ukrainian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party, the name under which it still exists today, and to which the authors of this letter belong.

The role played by the young Ukrainian socialist movement in the national renaissance is very significant. This movement has connected the question of national emancipation to all the problems of the emancipation of the proletariat; it has raised this question to the level of those political problems which can be solved by no other means than democratic struggle, by the development of class antagonism in Ukrainian society. Thus has progressed Ukrainian socialism, always following the same route, confirmed by the undoubted truth that in all present-day liberation movements, political or national — both being the result of the same evolution which saw the transformation of feudal states into modern capitalist states — the working class appears as the sole revolutionary and democratic power. This in effect is what is happening in the Ukrainian socialist movement, which is developing in struggle shoulder-to-shoulder with the workers’ movement in all of Russia.

The bourgeois Ukrainian movement adopted an altogether different position vis-à-vis the revolution. During the preceding period, when the revolutionary forces were organizing, the Ukrainian bourgeois movement, which turned with scorn from Ukrainian socialism, formed, it is true, two liberal parties (democratic and radical), but these parties dissolved at the end of the revolution.

In 1905 there appeared openly the first Ukrainian journal in Russia and although this journal was suppressed (despite the freeing of the press in the Russian Empire) a more or less free Ukrainian press could exist from 1906, although the censor created greater difficulties for it than for the Russian press.

The year 1906 saw the return of reaction and the gradual weakening of the socialist movement in Russia in general and in Ukraine in particular. The bourgeois Ukrainian movement, on the other hand, developed considerably, profiting from the liberties obtained by the revolution which it had done nothing to win. In the autumn of 1906, a large movement arose amongst the youth with the aim of nationalizing68 higher education and a campaign of petitions was launched which obtained over ten thousand signatures.

In the end the Ukrainian movement became infested with bourgeois ideas, socialism lost its former attraction, and antagonism between parties declined. To make this change the Ukrainian bourgeois parties fused into one and declared in 1907 that their press would no longer conduct inter-party struggle; socialist journalists were invited to work with them.69 The majority of them voluntarily accepted this invitation.

However the Ukrainian movement had acquired such strength during the revolution that it was represented in the first two Dumas by two large groups of a progressive nature. These groups found themselves under the influence of the bourgeois parties without being their direct representatives. The law of June 3, 1909, limiting the rights of voters was applied in such a way in Ukraine that there were no longer any Ukrainian deputies in the Duma. Elsewhere the socialist movement grew weaker day by day. The socialist intellectuals passed en masse into the ranks of the bourgeois movement which after the final victory of reaction had adopted the principle of “limited affairs,” that is to say it had entirely renounced political demands. The bourgeois movement always concerned itself with a cooperation, which united all the middle classes in seeking to fulfill domestic interests, and in organizing educational bodies whose development was constantly hindered by the government. Alongside this purely utilitarian outlook, the bourgeois movement also showed a modernist literary tendency, seeking to free itself from the conventions of the old Ukrainian “democratism”; this movement had extolled the cult of individualism, with an extreme and undisguised hatred of socialism.

These two new traits of the Ukrainian bourgeois movement contributed to the lowering of the level of its ideas which slowly continued to lose breadth. It reverted to a method of activity established during the somber period of the second part of the nineteenth century. It again completely submitted to Tsarism with a view to reconciliation and agreement with it. For its part the government reverted to its old ways and in order to destroy the Ukrainian movement it closed the educational institutions on even the weakest pretext, and to stop the Ukrainian press from having any effect in the province it persecuted newspaper subscribers. The well-known minister Stolypin, assassinated in Kyiv, declared that “the national and political tendencies of the Ukrainian movement are at this point so close that it is impossible to distinguish between them” and that the most innocent of educational bodies were at the same time “anti-statist” for “they tended to develop revolutionary tendencies at the very breast of the Russian people.”70 Stolypin’s declaration followed a circular to provincial governors ordering them to refuse registration to Ukrainian educational institutions and followed with a redoubling of persecution, which was called by the government press “words of gold.”

But the Ukrainian bourgeois press showed an extraordinary indifference to these events. It published articles claiming that the government “did not understand” the movement and the Ukrainian question; that it did not understand its importance from a cultural standpoint, even though teachers from around the world recognized that it was necessary to conduct education in the mother tongue. Only the Russian government, refusing to take account of this truth proclaimed by the entire world, obstructed the development of education amongst the Ukrainian people, contrary to the general interest and its own, and acted as if it were a mistake. In response to these assertions, repeated with an astonishing stubbornness, Tsarism relentlessly employed new repressions, augmenting the supplications of the Ukrainian bourgeois press. Russian liberals were favorable to this, having become increasingly chauvinistic in the course of the reaction.

In these circumstances Ukrainian Social-Democracy remained impotent, although its press continued to exist and to protest against bourgeois politics. But given the small number of workers’ organizations (Kyiv, Katerynoslav, Kharkiv) and the near total lack of intellectual elements, it was difficult for us, despite all our efforts, to break the influence of a bourgeois politics which finally reached complete and shameful political bankruptcy.

This bankruptcy started with the war. The Tsarist government, expecting the conquest of Austrian Ukraine to “liberate” the “Russian” Galicians, suppressed the whole Ukrainian press in the first days of the war.71 It closed nearly all of the Ukrainian scholarly establishments (at a time when they were nearly all closed already) and arrested and deported the best-known Ukrainian political personalities. The situation remained unclear until the end of 1914, but at the start of the following year the governor general of Kyiv outlawed all publications in the Ukrainian language as well as the use of Ukrainian orthography. It is said that the government saw this ban as the equivalent of imposing the decree of 1876 again, which it remembered and still considered to be in force. In any case, there had already been two years of hard fighting and all the tentative efforts at reviving the Ukrainian press had ended in fiasco.

The only organ actually representing the Ukrainian world in Russia and to the foreign press was the journal Ukrainskaia zhizn, published in Moscow in the Russian language. In reporting the war it took an apolitical and loyalist-patriotic attitude toward Russia.72

Thus it was that the Ukrainian movement in Russia found itself without a way out of its situation. The bloody conflict of the Great Powers in territory belonging to the Ukrainian people had caused the complete material ruin of the whole of Austrian Ukraine and part of western Russian Ukraine. As well as this the war had struck a hard blow at the Ukrainian liberation movement and had destroyed all it had gained, from both the cultural and the political points of view.

IIThe best proof of the eclipse of socialist conscience, provoked by the European war, is the credence widely given in certain socialist circles to demagogic theories circulated among the masses in order to conceal from them the real aims of the war of conquest. The representatives of official socialism did nothing to reveal to the people, sent to the killing-fields, the odious undercurrents of European diplomacy; quite the contrary, they accepted the ignoble theories created by the leaders as their own; they put all their energies, all their goodwill at the service of the government cause.

But the scale of the collapse of official socialism among the socialists of the Entente is vast; witness especially their attitude toward the despot Russia and toward the role which its barbaric government is allegedly destined to play in the “war of liberation.” Leaving aside the plight of Belgium and Serbia, which the Allied armies ought fully to restore, only Poland remains to be liberated by the governments of the Tsar and his allies when all this chattering is done. The manifesto of Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich serves as a base on which to re-create freely the triumph of Right and Justice.73

This blind and limitless confidence with which the Entente democracies receive the promises of the head of the Russian autocracy seems at times paradoxical, unbelievable even; it is unfortunately too well known to be called into question. The most abject regime in Europe has suddenly become, in the eyes of the democracies of the Entente, the chivalrous defender of the entire Slavonic race; all the miseries inflicted on Poland by the Russian government down the centuries have been forgotten. The prison-house of nationalities, as Russia was frequently called, has won over all those in France and England whose hearts are touched by the love of oppressed nations. The flaw in all this rhetoric about the noble role of Russia is that it hides under the cloak of grandiloquence the vulgar interest of people greedy for conquest. Yet it has lost nothing of its vigor today, even though the Russian government has done everything to tarnish an already suspect reputation and to demonstrate, by its reactionary policy, the emptiness of promises extracted from it at the beginning of the war. Ah, no doubt the Russian ministers risk nothing in raining down tirades of irony on the Germans who founded the Polish University in Warsaw, but their mockery loses much of its value when the Polish deputies in the Duma are not prepared to take seriously the fine promises of the Russian autocracy and reproach it for its hypocritical policy which allows to persist the old inequalities between Russian subjects and the Poles who live within the Empire and pretends to be ignorant of the grievances of the Polish population.

Now, the socialists of the Entente, blinded by their narrow nationalism, are not interested in the betrayal by Tsarism in its engagements toward Poland at the beginning of the campaign. They are still more indifferent to the situation in which the Russian government has placed the Ukrainian people. All that Allied public opinion has wanted to see in the autocracy of Moscow is a great empire, united by the common seal of race and language, with inexhaustible resources in terms of men, whose victorious troops march like striking lightening across the distance which separates Berlin from Petrograd to deliver a mortal blow to “Prussian militarism.” It is no exaggeration to say that it is this false impression which the Allies have nurtured about Russia which has determined their sympathy for the Muscovite autocracy. Even though this dream was not realized, even though the reverse occurred, even though Russia’s military prestige was seriously shaken, the West has continued nevertheless to consider Russia as a united country, indivisible, whose vast territory is peopled by one great “Russian” nation. The joy manifested by the French socialist press when the Russian troops occupied Galicia and Bukovyna had to be seen to be believed. They saw the event as the triumph of the Muscovite empire, at long last restored to national unity; the Austrian Ukrainians were seen by the French socialists simply as “Russians” living over the border. The English press of all shades of opinion, which before the war had devoted long articles to the Ukrainian question, thought nothing of remaining silent over the crimes of Tsarism in Galicia. It was only after the defeat suffered by the Russian troops in Austrian Ukraine that the scandalous conduct of the Petrograd government in Galicia and Bukovyna was judged a little more severely by the socialists of the Entente. But this judgment was inspired by other motives than the defense of Ukraine, ruined and devastated by the barbarians from the East. If Russia was reproached for her conduct in Galicia, famously described by the liberal deputy Maklakov, as a scandal of European proportions, it was only because her savage policies had contributed to her military defeat.74 As for the fate of poor Ukraine herself, the attack on the rights of her people, this left the socialists of the Entente unmoved.75

This conspiracy of silence organized by the Allies over the Ukrainian question gave the Russian government an advantage in that it left them a free hand in their fight against the national movement in Ukraine, while at the same time disarming the movement by considerably weakening its powers of resistance to the Muscovite oppressor. The politicians of Russian Ukraine had always considered Galicia as a corner of land where the Ukrainian people could have lived confident of freedom. They knew the cost of the efforts of the Tsar’s government to seize Austrian Ukraine, they knew about the seeds of corruption sown by the agents of Moscow to achieve this end and finish once and for all the Ukrainian threat. Yet they nevertheless renounced in advance all resistance and, under the menace of the iron fist, comforted themselves with the illusion that the annexation of Galicia by Holy Mother Russia would lead the Russian government to apply the same constitutional guaranties to the whole Ukrainian people as Austrian Ukraine had enjoyed under the domination of the Hapsburgs. They paid dearly for this illusion; unable to raise a single protest, they saw themselves condemned to the role of silent, passive witnesses to the downfall of the Ukrainian people on the other side of the border.

Today’s war has revealed the antagonism that exists between the bourgeois movement in Ukraine and the Russian political regime. There is no doubt that some of the goals pursued by Russian diplomacy in this war coincide with the vital economic interests of Ukrainian capital. Ukraine, with its fertile soil, holds first place in Russian agriculture; every year it sends its enormous stock of cereals abroad. According to the Russian economists, the center of economic life has for some time been shifting from north to south in Russia, that is, toward Ukraine. Thus, the young Ukrainian bourgeoisie cannot remain indifferent to the problem of free passage to the Mediterranean. Yet the overwhelming aim of all Russian imperial policy is to be master of the Straits.

However, the aspirations of the Russian government do not end there. Leaving aside its designs on Constantinople, the Muscovite autocracy wants to seize Galicia and Bukovyna in order to do away with the Ukrainian nation. It follows that the Tsar’s government, which wants to make itself master of Constantinople, is putting itself and its great army at the disposal of the economic interests of Ukrainian capital; then again, its vigorous thrust toward Austria, having no other aim but the conquest of Austrian Ukraine, threatens the nationhood of the whole of Ukraine. To put obstacles in the way of the national revival of the country is to attack its economic progress and sacrifice the vital interests of Ukrainian capital while leaving intact the colonial status to which Russia has reduced Ukraine. Tsarism thus accomplishes its double task: on the one hand, it protects the economic rise of capital in Ukraine; on the other hand, it jeopardizes its very future, attacking Galicia which it will always consider as its own national Piedmont.

Constantinople and Galicia, Russian imperialism and Ukrainian freedom, these are the contradictions which history sets before the Ukrainian bourgeoisie and which the latter tries to resolve by betraying its national ideal. The bourgeoisie prefers to abandon the vision of a free and independent Ukraine rather than sacrifice the bait of growing riches. Passive and apathetic before the great Muscovite empire, it reaches out to it, ready to accept any compromise, to bend to the harsh demands of its conqueror and its executioner. And, so that our readers may form a true impression of this slave mentality, we take the liberty of quoting a passage borrowed from Ukrainskaia zhizn, the only magazine which continues to appear after the suspension of all Ukrainian press at the beginning of the war:

The Ukrainians [declares this paper, with a certain pride] will not be fooled by suspect manoeuvres or any sort of foreign provocation. They will do their duty to the end. They will do so not only as soldiers on the battlefield, fighting those who have provoked war and violated all the rights of humanity, but also as simple civilians, called to contribute according to their strength to the great task which has fallen upon the Russian army.76

It seems pointless to seek out the nature of this “great task” which the Ukrainian bourgeoisie professes as its civic duty. Constantinople or Galicia? Our own goal, as Ukrainian socialists, is very different. The task of social democracy in Ukraine is to reawaken the socialist consciousness of the exploited so that they may understand the antagonism that exists between their class interests and the aggressive ambitions of Ukrainian imperialism. The only fitting socialist response would be an all-out struggle against militarism in Ukraine, be it “Ukrainian” or “Russian.” The triumph of democracy is the only possible guarantee under the capitalist regime against massacres and imperialist wars. This terrible war which has been unleashed on the world must make the Ukrainian workers understand that their own national bourgeoisie is sacrificing the interests of Ukrainian democracy, allowing the Russian government to conduct itself as master in Ukraine and to keep it in the grip of national and political slavery.

However, today’s war has brought politicians from the Central Powers into contact with the Ukrainian problem. And while Allied public opinion kept quiet about all signs of national life in Ukraine and even denied the existence of the Ukrainian problem, in Austria and Germany people were very sympathetic to the Ukrainian question; the press devoted long articles to it; everybody was talking about it. At the very beginning of the war, there was even a league formed under the name of “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine.” This was created by a few former socialists, of Russian Ukrainian origin, who claimed the right to represent Russian Ukraine to the governments of the Central Powers. Special funds were put at their disposal by the Austrian government to enlist them in making propaganda in favor of the cause of the Central Powers. It was these somewhat tainted funds which enabled the agents of the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” to go on a propaganda tour in Turkey and Bulgaria to persuade these countries to intervene in the conflict on the side of the Central Powers, on the pretext of helping the oppressed Ukraine. Such financial aid enabled the representatives of the Union, acting as paid agents of the Central Powers, to spread the hatred of war among the Turkish and Bulgarian peoples.

The situation of the Union was consolidated by the favorable reception it was given by the politicians of Austrian Ukraine. This is explained by the fact that in Austria (Galicia and Bukovyna), all the Ukrainian parties are united in a single organization under the banner of the “Austrian orientation” — whereas the “Russian orientation” is widespread among the Ukrainians in Russia.77 But while in Russia the loyalty of the Ukrainian population, persecuted and crucified by the Muscovite autocracy, is purely a matter of form, on the other side of the border, attached by constitutional ties to the monarchy of the Danube, Ukrainian loyalism has taken on an aggressively militaristic aspect, marked by propaganda in favor of the war against Russia, on the assumption that it will lead to the restoration of a free and independent Ukraine.

Yet the constitutional guarantees enjoyed by the Ruthenes in Austria did not stop the Poles taking the Ukrainian population under their political and administrative control, with the tacit consent of the government in Vienna. But the Austrian Ukrainians forget this reality in the exuberance of war: they imagined that the only goal of the Central Powers in this war was the liberation of Ukraine, and they put all their goodwill, all their courage at the service of Austrian imperialism. They believed, for example, that two thousand Ukrainian volunteers, enlisted in the Austrian army under the malevolent eye of the government in Vienna, were dying for the cause of Ukrainian independence. But most hideous of all is the energy and enthusiasm which Austrian Ukrainian Social-Democracy has expended on propagating these militaristic ideas, the collapse of the Ukrainian socialists in the face of the bourgeois political parties, even to the extent that the socialist organizations have merged with their class enemies.

However, the latest events have begun to sow seeds of doubt in the minds of the Austrian Ukrainians as to the value of this program. The territories of the Russian Ukraine (Volyn and Kholm), with a population of over two million, occupied by the Austrian army, have, on the orders of the Viennese government, been subjected to Polish and German administration. The latter, without any regard for the legitimate grievances of the Ukrainians, has notably proceeded to found Polish schools and has preferred to use Russian for administrative purposes, rather than the Ukrainian tongue. This example, only one of many, confirms the rumors currently circulating about a secret treaty agreed between the governments of the Central Powers on the matter of the reconstitution of Poland; it is alleged that, by virtue of this treaty, Poland would be attached to Austro-Hungary as a third state in the Hapsburg crown and that she would encompass, besides the former Polish state, Lithuania, together with White Russia, and the Ukrainian states of Volyn, Podilia, and Galicia.78 It goes without saying that such a solution to the problem of Ukrainian “reconstitution” inspires some fears among the Austrian Ukrainians who would be condemned, along with the Lithuanians, the White Russians, and certain elements of Russian Ukraine, to play the part of puppets in the hands of powerful neighbors within a reborn Poland. This shameful role as a destructive element within the new state does not seem to accord too well with the ideal of a free Ukraine. Moreover, Ukrainian Galicia is obsessed with threats of annexation to Russia. These threats provoke great anxiety among the Ukrainians of Austria.

Nevertheless, the Austrian Ukrainians continue to lend their support to the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine.” This only serves to confuse the Ukrainian question; it is further confused by the fact that the Union’s activities have received a cold reception in the Russian Ukraine. Our paper’s revelations about the shameful schemes of the “Union for the Liberation of Ukraine” and its financial resources, drawn from the secret funds of the Central Powers, which have been used as an excuse in a certain quarter of the French press and, above all, in the Russian press, to alarm public opinion with noisy rantings about the “treachery” of the Ukrainians, have led the Ukrainian bourgeoisie to declare their loyalty to the Muscovite autocracy.

However, the actions of the Union have had some positive results. It must be given credit for the interest displayed in the Ukrainian problem by military, governmental, and pan-Germanist circles in Germany, and, above all, by the partisans of outright war against Russia.