Currently under

construction.

We're adding features,

and making the site

available on phones.

Bear with us...

A few things are working.

Try them out

Currently under

construction.

We're adding features,

and making the site

available on phones.

Bear with us...

A few things are working.

Try them out

By Nancy Fraser & Federico Fuentes

14 February, 2024

Nancy Fraser is the Henry and Louise A. Loeb Professor of Philosophy and Politics at the New School for Social Research in New York, working on social, political and feminist theory. She is also the author of, among other works, Cannibal Capitalism: How Our System Is Devouring Democracy, Care, and the Planet—and What We Can Do About It. In this extensive interview, Fraser talks with Federico Fuentes for LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal about how transfers of natural wealth and care fit within modern imperialism, the role expropriation continues to play in capital accumulation, and the increasingly blurred nature of core-periphery boundaries under financialised capitalism.

Over the past century, the term imperialism has been used to define different situations and, at times, been replaced by concepts such as globalisation and hegemony. Does the concept of imperialism remain valid and, if so, how do you define it?

The term imperialism remains essential and I oppose replacing it with the other concepts. Globalisation, for example, is a buzzword. If by globalisation we simply mean the end of national economies and industrial policies, and the rise of neoliberalisation and elite capitalist powers shifting to a so-called free trade agenda, then that is fine. But imperialism refers to something else. Hegemony is an important concept in geopolitics. Generally speaking, it refers to the role an imperialist power (or bloc of powers) plays in organising the global space to facilitate imperialist extraction. But this refers to the political organisation of the global space. Again, this is different from imperialism — the concepts of hegemony and imperialism go together, but they are not the same. It is also trendy nowadays to hear talk of coloniality and decoloniality. This language seeks to underline how, even with the end of direct colonial rule, colonial hierarchies of cultural value remain in place. On its own, this idea is fine. But when it is used to replace the concept of imperialism — as it often is — it ends up putting the issue of global or imperial capitalism on the backburner. Yet that is where we need to start.

So, I am strongly in favour of retaining the term imperialism, even though I think we have to understand it better. Imperialism, in strictly economic terms, is about the transfer or extraction of value by certain powers from certain regions that are treated as hinterlands. But we can no longer just talk about extraction of economic value in the form of mineral wealth or surplus value. We also have to talk about extraction of ecological wealth and capacities for care from the periphery to capitalist core countries.

Discussions on the left regarding imperialism often refer to Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin’s book on the subject. How much of his book remains relevant today and what elements, if any, have been superseded by subsequent developments?

Lenin’s analysis of imperialism was an extremely powerful intervention at the time. But the concept of imperialism has been enriched since then. I also see some issues with his original concept.

Lenin specifically associated imperialism with financialisation. We are certainly living in a time of tremendous financialisation. But I would not say financialisation per se defines imperialism. Imperialism is about the transfers of both capitalised forms of wealth and what we could define as not yet fully capitalised forms of value, such as nature and care. Lenin also believed imperialism represented the last stage of capitalism. “Last stage” evokes Rosa Luxemburg’s idea that, at some point, capitalism will encompass everything and there will no longer be anything outside it. At that point, capitalism will no longer be able to expand and will cease to exist. Yet imperialism today involves both the incorporation of new forms of societal value into capitalist circuits of reproduction as well as expulsions. It includes for example, the expulsion of billions of people from the official economy into informal grey zones, from which capital syphons wealth.

Another difference is that the geography of value transfers no longer fits neatly onto the old First World/Third World map, with the Second World somewhere else. New geographical and political patterns, with new dimensions of wealth transfers, have emerged. For example, we have the deindustrialisation of the old core through the movement of manufacturing to so-called BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) countries. We have old colonial masters, such as Portugal, that have become dependent member states of the European Union, having to do whatever the Troika (International Monetary Fund, European Commission, and European Central Bank) tells them. And for the first time, significant populations in the Global North find themselves in a situation similar to those in the old periphery. There is a new form of imperialism that no longer has a clean geography of colonialists over here and colonised over there — it is more complicated.

Yet, despite these changes, imperialism remains the best term to refer to all this.

As you have noted, Marxist discussions on imperialism tend to strictly focus on the transfer of economic value. But you raise the need to consider the transfer of natural wealth and capacities for care. Could you explain how these transfers occur?

Let me start with the care economy, or what feminists called social reproductive labour. Social reproduction differs from the more general term societal reproduction, which encompasses everything that contributes to the continuation of a social formation. Social reproductive labour refers to the specific subset of activities that sustain daily replenishment and generational replacement of human beings who are the bearers of labour power — their biological reproduction, the provision and care work that sustains them on a daily basis, their socialisation and cultivation as members of specific classes in specific societies. These activities have historically been associated with women (although men have always performed some activities of reproductive nurturance, sustenance and care). And, historically, much of this activity (though not all of it) has occurred outside the circuits of the formal economy of capitalist societies. In fact, capitalism is unique in sharply separating waged work from social reproductive labour — often referred to as care. Yet the latter is necessary for the existence of waged work, the accumulation of surplus value and the functioning of capitalism. Wage labour could not exist in the absence of housework, child rearing, schooling, affective care and a host of other activities that help produce new generations of workers and replenish existing ones.

Historically, capital took for granted that there would always be a steady supply of labour power. But the conditions of early industrialisation were so destabilising that family conditions became basically impossible in many big industrialising cities of the capitalist core. That made the issue of social reproduction a political one. Later, wealthy countries with access to sufficient tax revenues created welfare states that assumed some public responsibility for social reproduction. But with neoliberalisation came disinvestment in social reproduction. Given women’s broadscale entry into paid work, the question became who was going to take care of the household, the children, the aged, the neighbourhood — all that so-called women’s work.

One strategy to fill the “care deficit” in wealthy countries was importing cheap care work from poor countries. Freeing up women’s wage labour in rich countries required commodifying social reproductive work. The result was a flood of migrant women workers to perform this paid care work. Governments in poor countries, desperate for hard currency, actively promoted this emigration for the sake of remittances [money sent by immigrants back to their country of origin]. But this meant migrants had to transfer their own social reproductive work onto other, still poorer caregivers, who in turn had to do the same, and on and on. What we got was a bumping down of the care deficit from richer to poorer families, from the Global North to the Global South.

This has become so widespread that it has been theorised as a new dimension of imperialism — what feminists call “global care chains”, which is a play on the more familiar term global commodity chains. The Filipino state, which depends on the export of women to do care work in Los Angeles, Israel, Gulf states, etc, is the poster child for this. I would recommend an article by Arlie Russell Hochschild, “Love and gold”, where she explains how love is the new gold. Instead of exporting mineral wealth, countries are now exporting this newly monetised commodity.

Much of the same applies to natural wealth. Much like social reproductive work, capital has always treated nature as something that can be freely or cheaply appropriated for capital accumulation. Whether it is silver, cotton, tobacco, sugar or cocoa, transfers of natural wealth were crucial to the rise of capitalism, even during the early stages of so-called mercantile or slave capitalism. Later, industrialisation in Europe, North America and Japan depended upon extractivism in the periphery: Manchester’s factories hummed due to the massive import of natural wealth from the American south and colonised regions.

The export of natural wealth has existed for a long time. But it has taken on a new dimension today due to the climate crisis.It is more apparent than ever that the issue is not just exporting natural wealth to the capitalist core but also exporting waste and the fallout of climate change to the periphery. We can no longer think of imperialism as taking good stuff from over there and using it here; we also have to think of dumping the bad stuff resulting from the seemingly good stuff over there. Of course, the idea that the fallout of climate breakdown can forever be exported elsewhere is an illusion, because the climate system is global. But it is communities over there who are currently bearing a hugely disproportionate share of the global environmental load.

That is why ecological imperialism is such an important and useful category. Some of the most exciting new works on imperialism focus not only on global care chains but theories of ecological load displacement and unequal ecological exchange. None of this obviates the older focus on economic value extraction, but it shows that too much Marxian analysis of imperialism unwittingly took on board the capitalist understanding of wealth and missed these other dimensions.

You also use the concept of expropriation, alongside exploitation, when analysing imperialism. Could you explain what you mean by this?

The classical Marxist definition of exploitation refers to a situation of paid labour, where labour is sold in the labour market and the worker receives compensation for their necessary labour time but not their surplus labour time. Worker’s wages only cover what is required to replenish their labour and produce new generations of workers, at least in theory. In this context, exploitation refers to the gap between the amount of value the worker produces and the amount they are compensated for their necessary labour time.

In contrast, expropriation, when talking about labour, refers to labour that is not even compensated for its necessary labour time. Prior to industrialisation, capital accumulation mainly occurred through the exploitation of unfree labour that was violently and brutally confiscated. Expropriation can also refer to the violent confiscation of land, animals and other forms of wealth. So, when I talk about expropriation, I am talking about the seizure of wealth — whether in the form of labour, land or other assets — that has been violently incorporated into circuits of capital accumulation. This is not a new idea: Luxemburg talked about something similar, as did David Harvey, who developed the concept of “accumulation by dispossession”.

Within traditional Marxism, there has been a tendency to think accumulation works overwhelmingly by exploitation. Yet expropriation has always been part of the story and continues to be so today. Far from being confined to the system’s beginnings, it is a built-in feature of capitalist society, just like exploitation. The system cannot accumulate without expropriation. It is not possible to turn everything into free labour that is exploited in factories and paid the necessary costs to continue reproducing workers. Moreover, capital has a deep-seated interest in confiscating labour and natural wealth to raise profits. That is why expropriation underlies exploitation.

How does expropriation differ from super-exploitation, which also refers to labour that is paid less than its necessary labour time?

Super-exploitation is also used to talk about how workers of colour are paid less than white workers and therefore face higher rates of exploitation. I do not see this as wrong but, in my opinion, this views the issue in purely economistic terms. Expropriation of labour is not just about extracting more value; it is also about status and hierarchy, and the fact that this labour is subjected to forms of coercion, violence, humiliation, etc, that are of a different order. Expropriation works not just as an economic mechanism of extraction, but through the political mechanism of coercion. Even in a country such as the United States, workers of colour are subjected to forced prison labour, police harassment, assault and even murder, as well as other forms of status denigration and humiliation. These are not unrelated to capital accumulation. That is why I view the category of super-exploitation as too economistic.

I would add that, historically, the exploitation-expropriation distinction has roughly corresponded to the global colour-line. While European populations, after an initial period of expropriation, filled the ranks of the exploited working class, it was populations of colour in the hinterlands and colonised regions that continued to be expropriated. You cannot understand exploitation in the capitalist core without understanding its relation to expropriation in the periphery. Black Marxist thinkers such as WEB Du Bois, in his great book Black Reconstruction, showed how the exploitation of the white industrial working classes in Europe and North America was inextricably entwined with the expropriation of Black enslaved workers.

What relative weight do mechanisms of imperialist expropriation and exploitation have today compared to the past?

Expropriation and exploitation have contributed to accumulation throughout the different phases of capitalist development, but in different ways. I am particularly interested in historicising the relationship between exploitation and expropriation during these different phases and looking at how the forms and relative weight of the two have changed over time.

For example, in financialised capitalism, debt has become a tremendously important mechanism of imperial extraction. It is used by global financial institutions to pressure states to slash social spending, enforce austerity and generally collude with investors in extracting value. Debt is also used to dispossess peasants in the Global South for corporate land grabs aimed at cornering supplies of energy, water, arable land and “carbon offsets”. And debt is crucial to accumulation in the core. For example, precarious service workers in the gig economy whose wages fall below the socially necessary costs of reproduction are forced to depend on expanded consumer credit.

At every level and in every region, debt is driving major new waves of expropriation. This has led to new, hybrid forms of expropriation and exploitation. For example, we have nominally free wage workers living in post-colonial countries so heavily burdened by sovereign debt that a huge amount of their labour goes to debt servicing. Something similar is occurring in wealthy regions: with the tremendous rise of consumer debt under neoliberalisation, workers who used to be merely exploited are now subject to forms of financial expropriation. These hybrid forms are blurring the old sharp division between enslaved Black expropriated workers and free exploited white workers. Now it is much muddier. That does not mean we do not have imperialism anymore; it is just more complicated to map these relations.

The original imperialist powers built their wealth and military might on colonial conquest and pillage of pre-capitalist societies. Have any new imperialist powers emerged since? And if so, what were the economic foundations of these new powers?

Leaving open the issue as to whether “actually existing” socialist states could have been defined as imperialist — which is a complicated question — there is no doubt in my mind that some post-Communist states are imperialist. The poster child for this is China. I believe imperialism is the right term to use to describe the extractivism China is practising in Africa. This is true even if China is not carrying this out in the same way that US or European corporations did; in China’s case, we are not dealing with conquest and direct colonial exploitation.

In light of what has occurred in financialised capitalism, can transnational enterprises now operate successfully without an institutional anchorage in an imperialist power?

Financialisation has led to a shift in state-corporation power dynamics, with corporations having more power and states, including powerful states, having less. Today we have gigantic global corporations whose wealth in many cases eclipses that of relatively substantial states. These corporate powers have been unleashed from the control of territorial states, often headquartering themselves in tax havens such as Andorra — hardly a capitalist power. They constantly push up against state power, even in the US, which is nominally the hegemonic state of our time (though if the US remains hegemonic, it is certainly a hegemonic state in steep decline). The US state does not control Apple or Google. So, we are no longer in a situation where we can really speak of companies that are “national champions” clearly located in a nation-state and which the state gives all kinds of breaks and advantages to it. It is a different ballgame now.

That said, I think it is too early to give a definitive answer as to whether transnational enterprises can operate without an institutional anchorage in an imperialist power. The US can still rely on the power of the US dollar, which is the world’s currency when it comes to the monetary system, the banking system, the ability to transfer funds, etc. Moreover, US property law has basically become international law in the form of the TRIPS [Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights] agreement. Katharina Pistor has a good book, The Code of Capital, which looks at how US legal understandings of property, dispute resolution, contracts law, etc have all gone global as an extension, if not exactly of US state power, of the US’ legal regime. Whether this means the US government can actually control Apple is a different question.

How should we understand the growing US-China rivalry in light of the fact that the two economies are more integrated than ever? And how do you view current dynamics within global capitalism given it is not just traditional imperialist powers, such as the US and Israel, launching full-scale wars, but also Russia, and even Turkey and Saudi Arabia, deploying military power beyond their borders?

There is a lot of testing of the US going on. Militarily, the US remains very powerful, although it is not the only state with nuclear weapons. Economically, it is a mixed bag. And morally, its credibility is very weakened. As for Israel’s current war on Gaza, as an American Jew, I have to say that I am outraged that the US has not helped stop this by simply turning off the spigot. Israel is a country where the US has a lot of leverage. But that is not the case everywhere.

For example, we have the rise of China as a great economic power trying to figure out exactly when and how to assert itself on the global political stage. This is still a work in progress: China is hovering on the brink, flexing a lot of muscle but still deciding whether, when, and how to step out. This has led people to question whether China will become a new hegemonic power or whether some kind of new multipolar arrangement will emerge. We also have Russia, which is very much a declining power with a rather weak hand, but one that [Russian president Vladimir] Putin — whatever else we might think of him — has played rather well. Russia punches well above its weight in world politics, with influence not just in bordering countries but in Syria, Africa and elsewhere. And we have China, Russia, Turkey, Iran and some other countries starting to form a block against the US. Meanwhile, the European Union is basically non-functional as a serious political player on the geopolitical level for all kinds of reasons such as internal divisions and the structure of the union.

As you said, the economies of China and the US are very integrated. That puts a break on things. But there are also wildcards in the mix, such as the looming possibility of a Trump presidency. In terms of disentangling the economies, we could see certain tariffs imposed. And we may see some new sabre rattling — though Trump, with his America First isolationism, is slightly more rational when it comes to foreign policy than the foreign policy establishment. But whatever happens, we are in for a very rocky ride. There are reasons to be very worried by the absence of any stable hegemony. The US is out of control and does not know what it is doing. This could lead it to do some very stupid things. These are dangerous times.

Do you see possibilities for building bridges between anti-imperialist struggles? More generally, in light of what we have discussed, what could 21st century anti-imperialism and anti-capitalist internationalism look like?

There are possibilities, but how likely they are to be realised is another question. As I said, we are living in dangerous times. We could at any moment slide into some kind of horrific nuclear or world war. We face planetary meltdown due to the ecological crisis. And there is tremendous precarity and insecurity in terms of livelihood, even in wealthy parts of the world.

Under these extreme conditions of crisis, in which normal certainties have broken down, many people are willing to reconsider what is politically feasible. This has opened space for those left-wing forces willing to think through the kind of new alliances we need for these times. But we have also seen the rise of right-wing — and in some cases proto-fascists or at least authoritarian — populists. These are all responses to the breakdown of bourgeois hegemony (in the Gramscian rather than geopolitic sense).

I have been thinking about these questions since [the] 2008 [Global Economic Crisis] and the Occupy movement [in 2011]. At times, I have been more optimistic about the prospects for an emancipatory left to build anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist alliances. At other times, it seemed the far right has been more successful in channelling dissatisfaction. But the point is that we have no other option but to fight for a new anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist internationalism — one that is feminist, anti-racist, democratic and green. All these adjectives point to legitimate existential concerns of people in motion. We are not in a position to say, for example, that struggles against police violence are less important than struggles against climate: for those experiencing police violence, nothing could be more important.

What gives me a little bit of hope is the fact that at the root of all these issues are not discrete, separate problems. Instead, they are all traceable to the same source, which I call “cannibal capitalism” in my latest book. I try to show how it is a built-in structural tendency of capitalist society to cannibalise nature, care, the wealth of subjugated peoples, and the energies and creativity of all working people. If we can get more people to understand these links, then broader alliances will begin to make sense. Somehow, we have to figure out how to put all these things together, without ranking oppressions. Ultimately, none of these distinct movements are powerful enough to make the kind of change we need on their own.

By Dominic Alexander

Counterfire

February 2 , 2024 -Edward Palmer Thompson, born a century ago on 3 February 1924, was not only one of the most important British Marxist historians but was also among the most important internationally. He is surely best remembered for his monumental work, The Making of the English Working Class (1963), which in charting the development of a political class consciousness among workers in England during the Industrial Revolution from the end of the eighteenth century through to the 1830s, has been praised and attacked in equal measure ever since.

Given all this argument, it is worth establishing just what the book’s core contribution was to the story of the working class, and to the history of political radicalism. The book begins with the English Jacobins of the 1790s and explores the religious and political traditions the radicals inherited from dissenters and other sources. It then moves from considering this relatively respectable milieu of literate artisans and shopkeepers to what can be gleaned about attitudes of the ‘unrespectable’ working class, whose participation in politics could appear as ‘as something of a mixture of manipulated mob and revolutionary crowd’.

The establishment routinely paid such people to attack their opponents, especially radicals, on the basis that the latter were a threat to the people’s liberty. Thus, In the 1790s, radical reformers might well be attacked by a ‘Church and King’ mob, but this changed in the course of the next couple of decades. As early as 1815, ‘it was not possible, either in London or in the industrial North or Midlands, to employ a ‘Church and King’ mob to terrorize the Radicals.’ The ruling class hold on the loyalty of the ‘unrespectable’ crowd had evaporated. This is one of the notable signs of growing class consciousness and hostility to the ruling class and the system.

In one respect, Thompson’s argument is about how the two, often mutually antagonistic, sections of eighteenth-century plebian society, the artisanal and the ‘disreputable’, both fed into what would become a self-conscious working class waging a mass struggle for radical democratic change by the 1830s with the Chartist movement. Explaining this massive shift in social alignments and political consciousness takes in the most detailed consideration of the social conditions and exploitation endured by all sections of the wider working classes during these years of the Industrial Revolution, as well as all the industrial and political agitations of the time.

In so doing, Thompson challenged a whole range of academic opinions about the period, from arguments that the working class benefited from industrialisation (they demonstrably did not), to long-standing dismissals of various radical figures and movements, such as the Luddites. The latter, in particular, Thompson showed to be far from blindly anti-technology or just ‘primitive’ trade unionists, but people capable of considerable feats of clandestine organisation and political-economic awareness.

The magnificence of the research and the vivid detail in the writing won many a reader over to Thompson’s argument, but aspects of it have remained controversial even among Marxists. The issues have been partly muddled by the passage of time. Thompson himself in later years wrote voluminously on contemporary politics, particularly through his anti-nuclear activism, but the positions taken in such essays need to be assessed separately from what he wrote in The Making. The development of historical research, the academic arguments engendered by the book, and Thompson’s disappointments with the New Left, all had an impact on his later writings.

It is necessary to go back to the original context for The Making to grasp Thompson’s intent. He had opponents in two directions, firstly the right-wing and liberal academic consensus, and secondly a version of Marxist analysis that has now largely been left behind. That was the typically mechanistic conception of social change and consciousness indebted to Stalinist Marxism. Whatever some may have later taken from the book, The Making itself remained fully materialist in its approach.

The period the book covers was long understood to be a dramatic one, and Thompson agreed that ‘the history of popular agitation during the period 1811-50’ suggests that ‘it is as if the English nation entered a crucible in the 1790s and emerged after the Wars [i.e.1815] in a different form’. For Thompson, this led on to a period in which a class-conscious working-class movement took shape by the 1830s. However, the period 1790-1815 also coincided with a ‘dramatic pace of change in the cotton industry’, so the assumption had been that the arrival of the modern factory system was the direct and automatic cause of the emergence of a militant working class: ‘the cotton-mill is seen as the agent not only of the industrial but also of social revolution, producing not only more goods but also the ‘Labour Movement’ itself.’ This deterministic view was what Thompson had set out to challenge.

To start with, he was quite right to point out that the mass of pre-factory hand-loom weavers, for example, ‘were as prominent in every radical agitation as the factory hands. And in many towns, the actual nucleus from which the labour movement derived ideas, organization, and leadership, was made up of ’a whole range of artisanal trades. Factory workers did not become the dominant core of the working class until at least the 1840s. In other words, there is not a straight read-off to be made from the new forces of production of the modern factory system to a class-conscious labour movement.

This is really what should be expected. No social formation arrives all at once, ready-made, but necessarily grows within already existing social relations, creating a whole host of contradictory dynamics and influences. Even so, Thompson was not in any way denying the significance of the new forces of production, indeed he notes in the course of the analysis being quoted here that: ‘Cotton was certainly the pace-making industry of the industrial revolution, and the cotton mill was the pre-eminent model for the factory-system’. Moreover, much of the book is concerned directly with the impact of the industrial revolution on all sections of the ‘labouring classes’, which had much to do with the rise of the range of radical dissent and protest in the period.

Thompson’s argument, however, is that nothing is automatic, and people can only pursue their struggles using all the available social resources. Thus the existing radical traditions inherited from the eighteenth century, many of them even preserving elements of the radicalism of the seventeenth-century Civil War period, fed into and helped to shape the working-class politics and consciousness of the 1830s. Although Thompson could later be interpreted as arguing that ‘culture’ was more important than the ‘economic base’ in determining consciousness, thus opening the way to postmodernist approaches that disappear the materiality behind social change altogether, that was clearly not what the argument of The Making was doing in 1963. Then, the target was Stalinist determinism, where ‘consciousness’ is held to reflect statically conceived economic structures.

The argument of The Making seems to me to be firmly in line with Marx’s oft-quoted view that: ‘Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.’ Thompson’s famous explanation of class in the Preface to the Making is sometimes criticised for leaning too heavily on the subjective side of the formation of class, but the material foundation of class is underlined as strongly here as it is throughout the book: ‘The class experience is largely determined by the productive relations into which men are born – or enter involuntarily’.

Class consciousness is, however, necessarily more dependent upon subjective factors: ‘We can see a logic in the responses of similar occupational groups undergoing similar experiences, but we cannot predicate any law. Consciousness of class arises in the same way in different times and places, but never in just the same way.’ Class itself is not a static structure in which people are simply slotted, but is something that happens: ‘class is a relationship and not a thing.’ This then is a powerful argument against the kind of academic sociology that splits the population into various strata, each of which can be defined as much by status indicators as economic position: ‘If we stop history at a given point, then there are no classes but simply a multitude of individuals with a multitude of experiences’.

However, class is a relationship of domination and exploitation, which unfolds over time. This renders different particular experiences of it comparable; thus hand-loom weavers and factory operatives came to understand, argued Thompson, that their experiences of class shared the same ‘logic’, regardless of other differences between them. This played out over the decades 1790-1830, and over different struggles, economic and political, in which radical and eventually early socialist views were increasingly common amongst workers of various sectors. Since class consciousness happens as a historical process, so it can also subsequently weaken, and even be overcome by the various material differences between sections of the working class. It must be continuously nurtured and revitalised.

Rather than undermining the Marxist understanding of the role of base and superstructure in society, Thompson in the Making seems to offer a properly dialectical conception of the way in which people come to understand the social relations in which they live their lives. Existing traditions of dissent and protest therefore played an important part in the formation of the new working-class consciousness of the nineteenth century. This is not to give ‘superstructural’ forces undue weight but to realise that what were subjective factors in one generation feed into the objective conditions of the next. In sum, Thompson was pointing out that what we do now matters because it lays down the conditions in which we and our successors will be working in the years to come. Apart from the theoretical arguments about class and consciousness, it seems very likely that this argument about the necessity and meaningfulness of activism is one of the main reasons so many readers have found the book to be inspirational.

The Making was by no means Thompson’s only important contribution to Marxist historiography. Throughout the rest of the 60s and 70s, he continued to work on the social history of the eighteenth century, showing that a century supposedly without class struggle was, in fact, brimming with it, and that while classes did not yet exist in the form they would come to take due to the industrial revolution, nonetheless, the pre-industrial period was characterised by conflict between the two poles of capital and labour.

Two classic articles, ‘Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism’ (1967) and ‘The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century’ (1971), were later followed by the book Whigs and Hunters (Penguin 1975), which found class conflicts raging in aspects of early eighteen-century English society where no one had thought to seek them before. His very final book was a tour de force of intellectual history, Witness Against the Beast: William Blake and the Moral Law (Cambridge: CUP, 1993), where Thompson unpicked Blake’s debt to seventeenth-century revolutionary religious radicalism through the obscure sects that survived to his time, carrying fossilised parts of that radical tradition with them.

The essays on eighteenth-century England were developed further and finally collected in the book Customs in Common (Merlin, 1991/2010). However, here there are concessions to very different approaches to history, and probably to the increasing volume of attacks on his earlier writing from the academic left, as well as the right. In some of the statements in this last book, Thompson does at points allow for consciousness to be formative of class itself in some sense.

This was surely in response to the postmodernist approaches that had been attacking the very root of the materialist account of history. For example, Joan Wallach Scott, in a passage seemingly directed at Thompson, insisted that while ‘the rhetoric of class appeals to the objective “experience” of workers, in fact such experience only exists through its conceptual organization; what counts as experience cannot be established by collecting empirical data but by analysing the terms of definition offered in political discourse’ such that ‘class and class consciousness are the same thing’. This dispiriting, pure idealism is not the position Thompson took in The Making, and would indeed have undermined the very basis of all the painstaking research Thompson had carried out for that and his subsequence books.

Thompson’s understanding of history was highly sensitive to the complexities of change, and how in new circumstances, people forge new relationships and ideas out of the materials, whether organisational or ideological, bequeathed by old circumstances. Yet, if ‘discourses’ really had total primacy, then no new ideas could ever be born, and certainly no new movements could ever have appeared. The Making, in contrast, was about a period where, demonstrably, new kinds of struggles and new ideas burst forth together. It was not the ideas that puppeted the people, but the workers and artisans who developed the ideas and ways of resisting their rulers and the ruthlessness of the new capitalism.

In a sense, by the 1990s, the arguments had come full circle. Thompson was originally arguing against a view of Marxism that saw ‘consciousness’ as merely a reflection of material circumstances. His project was to show that people were active, rather than simply reactive, in forging the shape of their struggles and thus that class consciousness was actively self-created. For a variety of reasons, not least the generational defeat of the left in the 1980s, academic fashion blew past this dialectical view. It landed on another absolute as untenable as the Stalinist thesis: the enthronement of language as the controller of all that is real. Unfortunately, we have not yet escaped that space. Thompson was endeavouring to find the dialectical midpoint. This would recognise the interplay of determination and agency, of consciousness and material constraints, where the potential for class struggle to change the world is found. The lesson of The Making is that what we do matters, but also that it is necessary to think to do; theory and practice are inextricably bound together.

{Note from the OUL: We understand that universal human rights is a topic of ongoing controversy, and those who profess them do not, at times, lives up to them, including the U.S. and China. But we think it important to study differing approaches, and China’s is often neglected. So we publish this piece in that context.]

By Jiang Jianguo

English Edition of Qiushi Journal

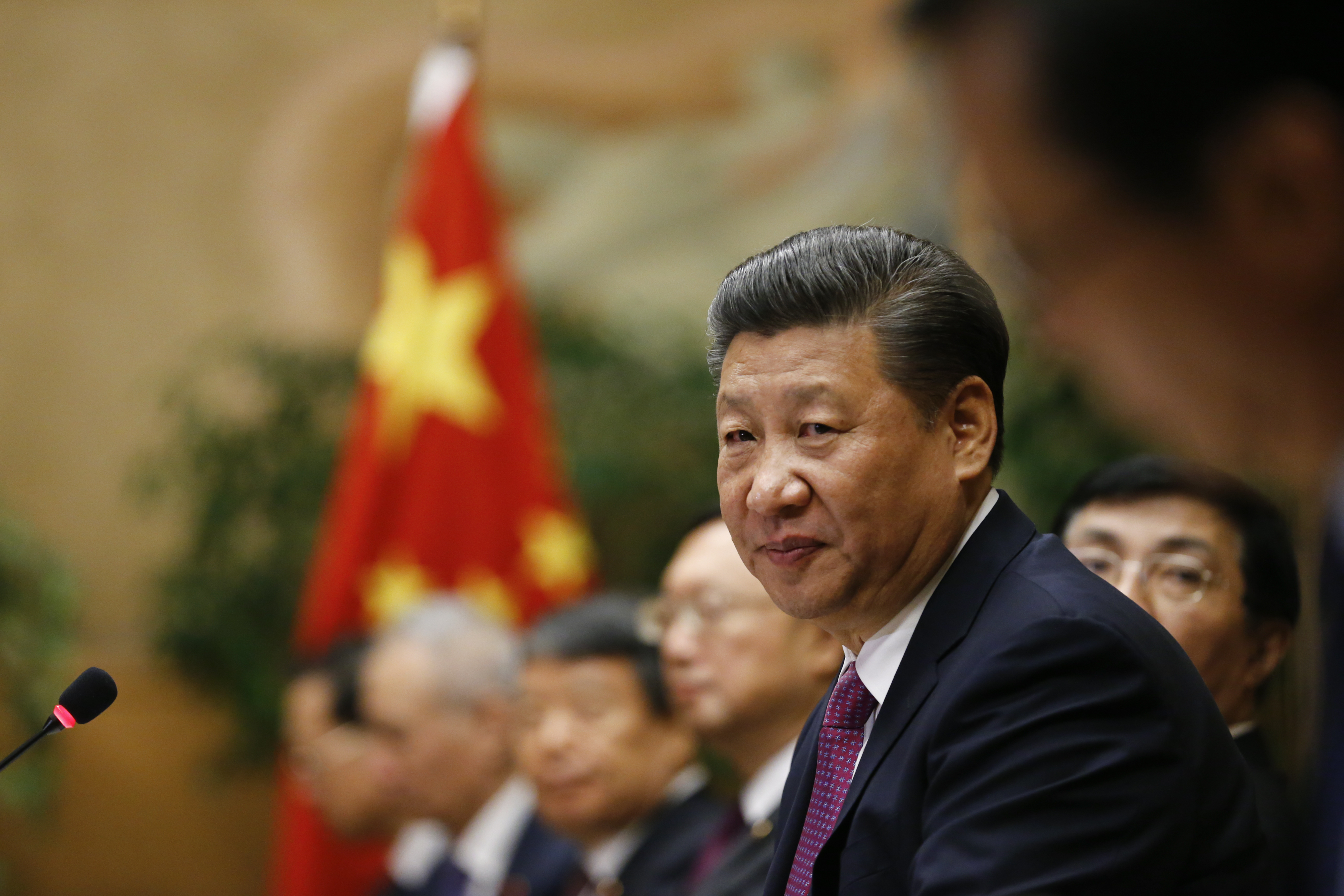

Jan 5, 2024 – Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in 2012, President Xi Jinping has made the development of human rights an important national governance priority. In a series of speeches and statements on the issue of respecting and protecting human rights, he has put forward in-depth answers to major questions concerning the nature of human rights, how best to advance human rights in China, and their governance on a global level.

From a theoretical viewpoint, President Xi has given shape to a contemporary Chinese perspective on human rights that is rooted in the “two integrations” (integrating the basic tenets of Marxism with China’s specific realities and with its fine traditional culture) while also reflecting the shared values of humanity. In practical terms, he has led the whole Party and all the Chinese people in following a Chinese path of advancing human rights that is right for the times and suited to China’s national conditions.

I. The rich content of the contemporary Chinese perspective on human rights

The contemporary Chinese perspective on human rights is in fact an in-depth summary developed by the CPC Central Committee with Xi Jinping at its core, and it reflects CPC’s longstanding experience of advancing human rights. This perspective offers deep insight into the global development and evolution of human rights and constitutes a well-founded outline of the living practice of human rights in contemporary China as well as a distillation of its fundamental positions and major viewpoints. It represents the all-new and comprehensive understanding that Chinese Communists have attained in the new era regarding the advancement of human rights.

As a major component of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, this perspective provides the fundamental principles we must follow in advancing human rights in the new era while also offering Chinese wisdom for the promotion of global human rights governance.

The leadership of the CPC is a fundamental guarantee for the advancement of human rights in China

Ensuring respect and protection for human rights has been a relentless pursuit of Chinese Communists. President Xi has pointed out that it is the CPC’s leadership and China’s socialist system that have determined the socialist nature of human rights in China and have ensured that the people run the country, that human rights are enjoyed by all people equally, and that human rights development is based on a holistic approach. This has enabled us to promote the all-around development of human rights and to better realize, safeguard, and promote the fundamental interests of the greatest majority of people. Only under the CPC’s leadership can the Chinese people enjoy still better and happier lives and gradually come to have broader, fuller, and more complete human rights.

The right to a happy life is the most important human right

The people are the CPC’s greatest source of confidence in governing and rejuvenating the country and the greatest source of motivation for advancing human rights. President Xi has emphasized that we must regard the people’s interests as our immutable aim, constantly strive to resolve the most practical problems that are of the greatest and most direct concern to the people, and do our utmost to ensure that people can live happy lives, as this is the most important human right of all. The CPC is committed to putting the people above all else and to upholding their principal position. It regards their aspirations for a better life as its primary goal. In every aspect of the entire process of advancing human rights, it strives to reflect the people’s aspirations, ensure their interests, protect their rights, and guarantee their wellbeing, and it works tirelessly to ensure a higher level of respect and protection for all basic rights of the Chinese people. Through its efforts, the CPC has been able to provide the people with a stronger sense of fulfillment, happiness, and security.

The rights to subsistence and development are foremost among basic human rights

Treating the rights to subsistence and development as first among basic human rights was an inevitable choice for the CPC given the needs of the people and China’s national realities. President Xi has stressed that subsistence is the foundation of all human rights. The Chinese people are profoundly aware that survival first and foremost requires freedom from poverty and hunger. Effectively guaranteeing the right to subsistence is the precondition and foundation for enjoying and advancing all other human rights. The right to development and the right to subsistence are closely tied together. The CPC fully safeguards people’s basic right to subsistence while also providing practical safeguards to ensure they enjoy their rights to equal participation and development.

Continue reading “–Promoting and Practicing a Contemporary Chinese Perspective on Human Rights”By Carl Davidson

Dec 20, 2023 – Since the recent publication of Liz Cheney’s new book, Wyoming’s former Member of Congress has been making the rounds of our top media outlets and news shows. If you have yet to watch one, do so. It’s well worth it.

Entitled ‘Oath and Honor: A Memoir and a Warning,’ the work takes a deep dive into former President Donald Trump’s attempted coup on Jan. 6, 2021. It not only covers that radical rupture with the usual ‘peaceful transfer of power’ in our country’s history, but Cheney also offers us a summary of the events that followed, especially the proceedings of the House of Representatives’s Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol.

But Cheney is making waves again because she’s delivering more than a history lesson. As her title states, she’s warning us that the battle against Trump and his GOP-turned-fascist party is far from over. In fact, her claim is that greater violent battles may occur in the upcoming presidential year, and we would do well to prepare.

We learn several things from her book we may not have known before, or at least, as the Bible says, we may have only known ‘through a glass darkly’ (1st Corinthians 13). First, Team Trump did not act alone. Second, it really was a coup attempt, complete with armed backup. Third, the attempt is ongoing and is getting worse. Fourth, Cheney had to organize her particular media experts and armed self-defense to survive, get the initial story out, and continue her battle today. Let’s go over them.

Team Trump was not alone. The fact that Trump and his staff, with the help of the Secret Service, pulled off a large rally on the morning of Jan. 6, 2021, was widely known, including Trump’s online assertion that it ‘will be wild.’ We could have guessed that it would march to the steps of the Capitol and even try to push through police lines. But what we did not know was a solid majority of House Republicans and a few GOP Senators had been organized in a deeper plot, one involving dozens of GOP-dominated state legislators as well. They were all in on it; they all knew it was illegal, fraudulent, or at least ‘extra-legal’ and unconstitutional, and they were willing to use violence to get their way.

Liz Cheney knew the vital technical details. She knew the GOP collaborators would have fake ballots of fake electors, and they would try to stuff them into the traditional mahogany box handed to Vice President Pence for the counting ceremony. Cheney conferred with the Senate and House parliamentarians and the Sergeants-at-Arms on how to thwart it. She succeeded, but barely so. The other technical detail was that with each state count that Pence reported, House GOPers could object, but unless a Senator also objected, there would be no debate. If there were debate, the Joint Session would be suspended until each House debated and voted the ‘objections’ up or down. They would then return to the Joint Session for Pence to continue. This adjourning could be repeated 50 times, possibly taking days or even more, ensuring chaos. In the chaos, Team Trump would try to throw the election to the states, where each state got one vote, and the GOP held the majority of states.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, the mob breached the Joint Session after only one vote, Arizona, and one Senator, Josh Hawley, casting a vote to force the end of the session. Cheney saw to it that the mahogany box was secured. She also had seen to her personal security. Her father, Dick Cheney, the former Vice President and Secretary of Defense, had warned her ahead of time to do so, and insisted on it. She used a trusted ex-Secret Service agent who had guarded her as a child to make sure she was always secure and protected as she moved about or in undisclosed places.

Dick Cheney also had a hand in getting all former living Secretaries of Defense to sign a widely publicized open letter warning of the necessity for a peaceful transfer of power.

Liz Cheney’s next steps were carried out closely and jointly with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi. They hardly knew each other before, but both knew exactly what had to be done: The Capitol had to be secured that day, and called back into session, even if in the late wee hours. In that session, they had to complete the Arizona debate and make sure there were no more. Still, even after the violence, 139 Houses GOPers stuck to the Trump plan and voted objections. But no Senator voted with them, meaning no interruption of the Joint Session. Under armed guard against any disruption, Cheney and Pelosi got it done. Pence finished the count, and the ceremony was completed. Biden would be sworn in on Jan. 20, 2021.

It really was an attempted coup. Trump insisted that his guards at the Jan. 6 rally turn off their weapon detectors because he knew large numbers of Oath Keepers and Proud Boys were armed. Luckily, the Secret Service was tactically split. Trump planned to lead the assault himself, but the agents in his limo forcibly restrained him and delivered him back to the White House. The mob who did get into the Capitol, and a trained handful of them knew their several tasks: seize and detain Nancy Pelosi, overwhelm the Sergeants at Arms, get the mahogany box, and seize and detain Mike Pence. Pelosi, working with Liz Cheney, thwarted each tactical move.

But there was more. In the days before Jan. 6, Trump had fired and replaced several top Pentagon officials and replaced them with his hitmen with zero qualifications, other than personal fealty to him, to hold those offices. He was assisted by Gen Micheal Flynn, who he had pardoned earlier. Along with Roger Stone, Flynn was Trump’s liaison with the Oathkeepers and other armed units. Trump also acted to confuse and limit the intervention of the National Guard. Once the Electoral College count was thwarted, the plan was to use the Insurrection Act to put the country under martial law.

The ‘Election Denial’ attempt was, and remains, ongoing. By Jan. 11, even though Trump had only a few days left in office, Democrats introduced Articles of Impeachment. It passed the House but with only 10 Republicans voting for it. The GOP majority, while offering a variety of excuses, still stuck with Trump. Cheney was hopeful that Senator Mitch McConnell would back it in the Senate, but in the end, he wavered, and that meant less than the required two-thirds. In the following weeks, GOP leader Kevin McCarthy went to Mar-a-Lago to flip-flop from his panicked Jan. 6 statements and get back on Trump’s side. The reason? His main job in the GOP was raising money. As a result of the coup attempt, many large corporate donors let it be known that funds to the ‘Freedom Caucus’ and its coup-plotting allies were drying up. The only other major source was Trump’s massive small donor lists. The price of access? McCarthy had to kiss ‘the Don’s’ ring and work to bring him back to the White House. Liz Cheney knew the Freedom Caucus were, for the most part, all surrendering and would work to sabotage any future joint investigation.

Cheney knew the full truth had to come out, and it wouldn’t be easy. With the prospect of a bicameral investigation cut off, Nancy Pelosi decided on the next best step: a bipartisan House Committee. She made an offer to McCarthy to name five Republicans to it. He did, but Pelosi objected to two of them as demagogic hacks, Reps Jim Jordan and Jim Banks, and told him to pick two more. Instead, McCarthy withdrew all five, leading her to quip that ‘Kevin won’t take ‘yes’ for an answer.’ But Pelosi was not to be stopped and instead asked Liz Cheney, and while Liz was a bit surprised, she readily agreed and helped pick one more Republican, Rep Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, who had stood against all the coup ploys. Pelosi had named Rep Bennie Thompson of Mississippi to chair the Select Committee, but then asked Cheney to be the vice chair. Somewhat surprised, Liz agreed.

From the start, Cheney knew the Select Committee had to be different. The last thing she wanted to see was a typical House hearing with dozens of reporters, glaring TV lights, and prima donna speakers trying to wring all the stage glamour they could out of an allotted five minutes. Average Americans would tune out. So, working closely with her husband, Philip Perry, an experienced trial lawyer, they planned a radical departure from the average hearing. In addition to legal experts, they hired top film and TV directors. They wanted a series of storyboards drawn up, each featuring a key element of the attempted coup. They wanted it to unfold as a dramatic series, with growing insights and suspense, with only the witnesses in the limelight. Moreover, they wanted nearly all the testimony to come from Republicans themselves, especially those who worked close to Trump and had initially supported him inside the Oval Office or his cabinet. And for any fearful for their lives, they had to do the recordings in highly secure facilities—and with no leaks.

As we know, Thompson and Cheney were successful and powerfully so. The Hearings became among the most widely watched and the most credible that anyone could name. Trump and the GOP attacked it as partisan trash, but the claim didn’t fly. All the testimony did indeed come from their own people. It did cause Liz Cheney to be purged from all her posts in Congress and then to be removed from Congress by a Trump diehard who defeated her in the next race in Wyoming. It didn’t matter.

Liz Cheney now probably has more political clout than she ever has had. And we need to note that she is still a solid right-wing conservative with a 95% rating by those who measure such things. The difference is in the remaining five percent: she is an anti-fascist who sticks by the Constitution and her oath to defend it. She is not only making the rounds to every media forum she can to promote her book and tell the story behind it, Cheney has also formed a new PAC, The Great Task. Its aim is not simply to keep Trump out of the Oval Office, or any office. It is also organizing Republicans, Democrats, and Independents to take down every Trump enabler, not only in Congress but also in every state legislature. And if it means endorsing progressive Democrats to do so, so be it.

This last point has considerable importance for the left. We are not in a ‘united front’ with Liz Cheney, or any formal grouping along those lines. We know her politics too well, and there are too many points of importance to sweep under any rug. But in the current conjuncture and its terrain, we do share common ground and a common goal: the routing of the MAGA fascists in the upcoming elections at every level and in future rounds as well. We can encourage Republicans we know at the base, people we know who are not likely to join our coalitions and projects but who might join hers. Things will undoubtedly change in the future, and for that matter, Liz Cheney may change, too. Nothing in the Universe stands still. But for now, work on the great task at hand.

by Gabriel Rockhill and Zhao Dingqi

Monthly Review

(Dec 01, 2023)

Gabriel Rockhill is executive director of the Critical Theory Workshop/Atelier de Théorie Critique and professor of philosophy at Villanova University in Pennsylvania. He is currently completing his fifth single-author book, The Intellectual World War: Marxism versus the Imperial Theory Industry (Monthly Review Press, forthcoming). Zhao Dingqi is an assistant researcher at the Institute of Marxism, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and the editor of World Socialism Studies.

This interview was originally published in Chinese in the eleventh volume of World Socialism Studies in 2023. It has been lightly edited for MR.

Zhao Dingqi: During the Cold War, how did the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) conduct the “Cultural Cold War”? What activities did the CIA’s Congress for Cultural Freedom carry out, and what impact did it have?

Gabriel Rockhill: The CIA undertook, along with other state agencies and the foundations of major capitalist enterprises, a multifaceted cultural cold war aimed at containing—and ultimately rolling back and destroying—communism. This propaganda war was international in scope and had many different aspects, only a few of which I touch on below. It is important to note at the outset, however, that in spite of its extensive reach and the ample resources dedicated to it, many battles have been lost throughout this war.

To take but one recent example that demonstrates how this conflict continues today, Raúl Antonio Capote revealed in his 2015 book that he worked for the CIA for years in its destabilization campaigns in Cuba targeting intellectuals, writers, artists, and students. Unbeknownst to the governmental agency known as “the Company,” however, the Cuban university professor it had slyly honey-potted into promoting its dirty tricks was actually pulling one over on the cocksure master spies: he was working undercover for Cuban intelligence.1 This is but one sign among many others that the CIA, in spite of its various victories, is ultimately fighting a war that proves hard to win: it is attempting to impose a world order that is inimical to the overwhelming majority of the globe’s population.

One of the centerpieces of the cultural cold war was the Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), which was revealed in 1966 to be a CIA front.2 Hugh Wilford, who has researched the topic extensively, described the CCF as nothing short of one of the largest patrons of art and culture in the history of the world.3 Established in 1950, it promoted on the international scene the work of collaborationist academics such as Raymond Aron and Hannah Arendt over and against their Marxian rivals, including the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. The CCF had offices in thirty-five countries, mobilized an army of around 280 employees, published or supported some fifty prestigious journals around the world, and organized numerous art and cultural exhibitions, as well as international concerts and festivals. During its lifetime, it also planned or sponsored some 135 international conferences and seminars, working with a minimum of 38 institutions, and it published at least 170 books. Its press service, Forum Service, broadcast, free of charge and all over the world, reports from its venal intellectuals in twelve languages, which reached six hundred newspapers and five million readers. This vast global network was what its director, Michael Josselson, called—in an expression reminiscent of the Mafia—“our big family.” From its Paris headquarters, the CCF had at its disposal an international echo chamber to amplify the voice of anticommunist intellectuals, artists, and writers. Its budget in 1966 was $2,070,500, which corresponds to $19.5 million in 2023.

Josselson’s “big family” was, however, just a small part of what Frank Wisner of the CIA called his “mighty Wurlitzer”: the international jukebox of media and cultural programming controlled by the Company. To take but a few examples of this gargantuan framework for psychological warfare, Carl Bernstein marshaled ample evidence to demonstrate that at least four hundred U.S. journalists worked surreptitiously for the CIA between 1952 and 1977.4 Following these revelations, the New York Times undertook a three-month investigation and concluded that the CIA “embraced more than eight hundred news and public information organizations and individuals.”5 These two exposés were published in establishment venues by journalists who themselves operated in the same networks they were analyzing, so these estimates were likely low.

Arthur Hays Sulzberger, the director of the New York Times from 1935 to 1961, worked so closely with the Agency that he signed a confidentiality agreement (the highest level of collaboration). William S. Paley’s Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) was unquestionably the CIA’s greatest asset in the field of audiovisual broadcasting. It worked so intimately with the Company that it installed a direct phone line to CIA headquarters that was not routed through its central operator. Henry Luce’s Time Inc. was its most powerful collaborator in the weekly and monthly arena (including Time—where Bernstein later published—Life, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated). Luce agreed to hire CIA operatives as journalists, which became a very common cover. As we know from the Task Force on Greater CIA Openness, convened by CIA Director Robert Gates in 1991, these types of practices continued unabated after the revelations mentioned above: “PAO (Public Affairs Office) [of the CIA] now has relationships with reporters from every major wire service, newspaper, news weekly, and television network in the nation.… In many instances, we have persuaded reporters to postpone, change, hold, or even scrap stories.”6

The CIA also gained control of the American Newspaper Guild, and it became the owner of press services, magazines, and newspapers that it used as cover for its agents.7 It has placed officers in other press services, such as LATIN, Reuters, the Associated Press, and United Press International. William Schaap, an expert on governmental disinformation, testified that the CIA “owned or controlled some 2,500 media entities all over the world. In addition, it had its people, ranging from stringers to highly visible journalists and editors, in virtually every major media organization.”8 “We ‘had’ at least one newspaper in every foreign capital at any given time,” one CIA man told journalist John Crewdson. Furthermore, the source related, “those that the agency did not own outright or subsidize heavily it infiltrated with paid agents or staff officers who could have stories printed that were useful to the agency and not print those it found detrimental.”9 In the digital age, this process has of course continued. Yasha Levine, Alan MacLeod, and other scholars and journalists have detailed the extensive involvement of the U.S. national security state in the realms of big tech and social media. They have demonstrated, among other things, that major intelligence operators occupy key positions at Facebook, X (Twitter), TikTok, Reddit, and Google.10

The CIA has also deeply infiltrated the professional intelligentsia. When the Church Committee released its 1975 report on the U.S. intelligence community, the Agency admitted that it was in contact with “many thousands” of academics in “hundreds” of institutions (and no reform since has prevented it from pursuing or expanding this practice, as confirmed by the 1991 Gates Memo mentioned above).11 The Russian Institutes at Harvard and Columbia, like the Hoover Institute at Stanford and the Center for International Studies at MIT, were developed with direct support and oversight by the CIA.12

A researcher at the New School for Social Research recently brought to my attention a series of documents confirming that the CIA’s heinous MKULTRA project engaged in research at forty-four colleges and universities (at least), and we know that a minimum of fourteen universities participated in the infamous Operation Paperclip, which brought some 1,600 Nazi scientists, engineers, and technicians to the United States.13 MKULTRA, for those unfamiliar with it, was one of the Agency’s programs that engaged in sadistic brainwashing and torture experiments in which subjects were administered—without their consent—high doses of psychoactive drugs and other chemicals in combination with electroshocks, hypnosis, sensory deprivation, verbal and sexual abuse, and other forms of torture.

The CIA has also been deeply involved in the art world. For instance, it promoted U.S. American art, particularly Abstract Expressionism and the New York art scene, over and against Socialist Realism.14 It funded art exhibits, musical and theatrical performances, international art festivals, and more in a bid to disseminate what was touted as the free art of the West. The Company has worked closely with major art institutions in these endeavors. To take but a single telling example, one of the major CIA officers involved in the cultural cold war, Thomas W. Braden, was the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) executive secretary before joining the Agency. MoMA’s presidents have included Nelson Rockefeller, who became the super-coordinator for clandestine intelligence operations and allowed the Rockefeller Fund to be used as a conduit for CIA money. Among MoMA’s directors, we find René d’Harnoncourt, who had worked for Rockefeller’s wartime intelligence agency for Latin America. John Hay Whitney of the eponymous museum and Julius Fleischmann sat on MoMA’s board of trustees. The former had worked for the CIA’s predecessor organization, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), and allowed his charity to be used as a conduit for CIA money. The latter served as the president of the CIA’s Farfield Foundation. William S. Paley, the president of CBS and one of the major figures in U.S. psychological warfare programs, including those of the CIA, was on the members’ board of MoMA’s International Program. As this web of relations indicates, the capitalist ruling class works closely with the U.S. national security state in order to tightly control the cultural apparatus.

Many books have been written on the U.S. state’s involvement with the entertainment industry. Matthew Alford and Tom Secker have documented that the Department of Defense has been involved in supporting—with complete and absolute censorship rights—a minimum of 814 movies, with the CIA clocking in at a minimum of 37 and the FBI 22.15 Regarding TV shows, some of which have been very long running, the Department of Defense totals 1,133, the CIA 22, and the FBI 10. Above and beyond these quantifiable cases, there is, of course, the qualitative relationship between the national security state and Tinseltown. John Rizzo explained as much in 2014: “The CIA has long had a special relationship with the entertainment industry, devoting considerable attention to fostering relationships with Hollywood movers and shakers—studio executives, producers, directors, big-name actors.”16 Having served as the Deputy Counsel or Acting General Counsel of the CIA for the first nine years of the war on terror, during which time he was intimately involved in overseeing the global rendition, torture, and drone-assassination programs, Rizzo was well placed to understand how the culture industry could provide cover for imperial butchery.

These activities and many more reveal one of the primary features of the U.S. empire: it is a veritable empire of spectacles. One of its principal focal points has been the war for hearts and minds. To this end, it has established an expansive global infrastructure in order to engage in international psychological warfare. The near absolute control it exercises over mainstream media has been clearly visible in the recent drive to garner support for the U.S. proxy war against Russia in Ukraine. The same is true for its virulent 24/7 anti-China propaganda. Nevertheless, thanks to the work of so many valiant activists and the fact that it is working against reality itself, the empire of spectacles is incapable of completely controlling the narrative.17

ZD: You mention in one of your articles that CIA agents were keen on reading the French critical theories of Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, Pierre Bourdieu, and others. What is the reason for this phenomenon? How would you rate French Critical Theory?

GR: One important front in the cultural war on communism has been the intellectual world war, which is the topic of a book that I am currently completing for Monthly Review Press. The CIA has played a very significant role, but so have other governmental agencies and the foundations of the capitalist ruling class. The overall objective has been to discredit Marxism and undermine support for anti-imperialist struggles, as well as actually existing socialism.

Western Europe has been a particularly important battleground. The United States had emerged from the Second World War as the dominant imperial power. In order to try and exercise global hegemony, it was intent on enrolling the former leading imperialist powers in Western Europe as junior partners (as well as Japan in the East). However, this proved to be particularly difficult in countries like France and Italy, which had robust and vibrant communist parties. The U.S. national security state therefore launched a multipronged assault to infiltrate political parties, unions, organizations of civil society, and major news and information outlets.18 It even set up secret stay-behind armies, which it stocked with fascists, and made plans for military coups if the communists ever came to power through the ballot box (these armies were later activated in the post-1968 strategy of tension: they committed terrorist attacks against the civilian population that were blamed on communists).19

On the more explicitly intellectual front, the U.S. power elite supported the establishment of new educational institutions and international networks of knowledge production that were decidedly anticommunist in the hopes of discrediting Marxism. It provided uplift—meaning promotion and visibility—to intellectuals who were openly hostile to historical and dialectical materialism, while simultaneously running heinous slander campaigns against figures like Sartre and Beauvoir.20

It is within this precise context that French theory needs to be understood, at least partially, as a product of U.S. cultural imperialism. The thinkers affiliated with this label—Foucault, Lacan, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, and many more—were associated in various ways with the structuralist movement, which largely defined itself in opposition to the most prominent philosopher of the preceding generation: Sartre.21 The latter’s Marxian orientation from the mid-1940s onward was generally rejected, and anti-Hegelianism—a shibboleth for anti-Marxism—became the order of the day. Foucault, to take but one telling example, condemned Sartre as “the last Marxist” and claimed that he was a man of the nineteenth century who was out of step with the (anti-Marxist) times, represented by Foucault and other theorists of his ilk.22

While some of these thinkers gained significant notoriety within France, it was their promotion in the United States that catapulted them into the international limelight and made them into required reading for the global intelligentsia. In a recent article in Monthly Review, I detailed some of the political and economic forces at work behind the event that is widely recognized as having inaugurated the era of French theory: the 1966 conference at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which brought together many of these thinkers for the first time.23 The Ford Foundation, which had been cofunding the CCF with the CIA and had many intimate ties to the Agency’s propaganda endeavors, funded the conference and other subsequent activities to the tune of $36,000 ($339,000 today). This is a truly extraordinary amount of money for a university conference, not to mention the fact that press coverage of the event was assured by Time and Newsweek, which is virtually unheard of in academic settings like these.24

The capitalist foundations, the CIA, and other governmental agencies were interested in promoting radically chic work that could serve as an ersatz for Marxism. Since they could not simply destroy the latter, they sought to foster new forms of theory that could be marketed as cutting edge and critical—though devoid of any revolutionary substance—in order to bury Marxism as passé. As we now know from a 1985 CIA research paper on the topic, the Agency was delighted with the contributions of French structuralism, as well as the Annales School and the group known as the Nouveaux Philosophes (New Philosophers). Citing in particular the structuralism affiliated with Foucault and Claude Lévi-Strauss, as well as the methodology of the Annales School, the paper draws the following conclusion: “we believe their critical demolition of Marxist influence in the social sciences is likely to endure as a profound contribution to modern scholarship.”25

Regarding my own evaluation of French theory, I would say that it is important to recognize it for what it is: a product—at least in part—of U.S. cultural imperialism, which seeks to displace Marxism by an anticommunist theoretical practice that indulges in bourgeois cultural eclecticism and mobilizes discursive pyrotechnics in order to create imagined revolutions in discourse that change nothing in reality. French theory rehabilitates and promotes, moreover, the work of anticommunists like Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, thereby attempting discreetly to redefine radical as radically reactionary.

Continue reading “Imperialist Propaganda and the Ideology of the Western Left Intelligentsia: From Anticommunism and Identity Politics to Democratic Illusions and Fascism”The federal government abandoned Reconstruction in 1877, but Black people didn’t give up on the moment’s promise.

By Peniel E. Joseph

The Atlantic, December 2023

Editor’s Note: This article is part of “On Reconstruction,” a project about America’s most radical experiment.

The civil war produced two competing narratives, each an attempt to make sense of a conflict that had eradicated the pestilence of slavery.

Black Americans who believed in multiracial democracy extolled the emancipationist legacy of the war. These Reconstructionists envisioned a new America finally capable of safeguarding Black dignity and claims of citizenship. Black women and men created new civic, religious, political, educational, and economic institutions. They built thriving towns and districts, churches and schools. In so doing, they helped reimagine the purpose and promise of American democracy.

For a time after the war, Black Reconstructionists also shaped the American government. They found allies in the Republican Party, where white abolitionists hoped to honor freedpeople’s demands and to create a progressive country in which all workers earned wages. Republicans in Congress pushed through amendments abolishing slavery, granting citizenship, and giving Black men the ballot. Congress also created the Freedmen’s Bureau, which offered provisions, clothing, fuel, and medical assistance to the formerly enslaved, and negotiated contracts to protect their newly won rights. With backing from the Union army, millions of Black people in the South received education, performed paid labor, voted in presidential elections, and held some of the highest offices in the country—all for the first time.

Black Reconstructionists told the country a new story about itself. These were people who believed in freedom beyond emancipation. They shared an expansive vision of a compassionate nation with a true democratic ethos.

Those who longed for the days of antebellum slavery felt differently. Advocates of the Lost Cause—who believed that the South’s defeat did nothing to diminish its moral superiority—sought to “redeem” their fellow white citizens from the scourge of “Negro rule.” Redemptionists did more than offer a different story about the nation. They demanded that their point of view be sanctified with blood. They threatened the nation’s infrastructure and institutions, and backed up their threats with violence.

In a sense, the work of Reconstruction never ended, because the goal of a multiracial democracy has never been fully realized.

The Redemption campaign was astoundingly successful. Intimidation and lynchings of Black voters and politicians quickly reversed gains in turnout. Reprisals against any white person who supported Black civil rights largely silenced dissent. This second rebellion hastened the national retreat from Reconstruction. Federal troops effectively withdrew from the Confederate states in 1877. White southerners soon dominated state legislatures once again, and passed Jim Crow laws designed to subjugate Black people and destroy their political power.

The official Reconstruction timeline usually ends there, in 1877. But this implies that the Reconstructionist vision of American democracy ceased to exist, or went dormant, without the backing of federal troops. Instead, we should consider a long Reconstruction—one that stretches well beyond 1877, and offers a view that transcends false binaries of political failure and success.

This view allows us to follow the travails of the Black activists and ordinary citizens who kept the struggle for freedom and dignity alive long after the Republican Party and white abolitionists had abandoned it. Black institutions, including the church, the schoolhouse, and the press, kept public vigil over promises made, broken, and, in some instances, renewed during the long march toward liberation. Their stories show that freedom’s flame, once boldly lit, could not be extinguished by the specter of white violence.

The concept of a long Reconstruction recognizes that a nation can be two things at once. After 1877, freedom and repression journeyed along parallel paths. Black Americans preserved a vision of a truly free nation in an archipelago of communities and institutions. Many of them exist today, and continue their work. This, perhaps, is the most important reason to resist the idea that Reconstruction ended when the North withdrew from the South: In a sense, the work of Reconstruction never ended, because the goal of a multiracial democracy has never been fully realized. And America has made its greatest gains toward that goal when it has rejected the Redemptionist narrative.