Currently under

construction.

We're adding features,

and making the site

available on phones.

Bear with us...

A few things are working.

Try them out

Currently under

construction.

We're adding features,

and making the site

available on phones.

Bear with us...

A few things are working.

Try them out

September 26, 2011 — First posted at Cuba’s Socialist Renewal, posted at Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal with permission — Cooperatives and Socialism: A Cuban Perspective is a new Cuban book, published in Spanish earlier this year. This important and timely compilation is edited by Camila Piñeiro Harnecker (pictured above). Avid readers of Cuba’s Socialist Renewal will recall that I translated and posted a commentary by Camila, titled “Cuba Needs Changes” [also available at Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal], back in January. Camila lives in Cuba and has a degree in sustainable development from the University of Berkeley, California. She is a professor at the Centre for Studies on the Cuban Economy at Havana University, and her works have been published both in Cuba and outside the island.

Camila hopes her book may be published in English soon. In the meantime, she has kindly agreed to allow me to translate and publish this extract from her preface to Cooperatives and Socialism with permission from a prospective publisher. I hope that sharing this extract with readers will make you want to read the whole book. If it does become available in English I’ll post the details here. If you read Spanish you can download the 420-page book as a PDF here or here.

At the end of the text you’ll find the footnotes and table of contents, translated from the Spanish — Marce Cameron, editor Cuba’s Socialist Renewal

By Camila Piñeiro Harnecker, translated by Marce Cameron

This book arises from the urgent need for us to make a modest contribution to the healthy “birth” of the new Cuban cooperativism and its subsequent spread. Given that cooperatives are foreshadowed as one of the organisational forms of labour in the non-state sector in the Draft Economic and Social Policy Guidelines of the Sixth Cuban Communist Party Congress, the Dr. Martin Luther King Memorial Centre approached me to compile this book. The Centre has made an outstanding contribution to popular education aimed at nurturing and strengthening the emancipatory ethical values, critical thinking, political skills and organisational abilities indispensable for the conscious and effective participation of social subjects. The Centre considers it timely and necessary to support efforts to raise awareness about a type of self-managed economic entity whose principles, basic characteristics and potentialities are unknown in Cuba. There is every indication that such self-managed entities could play a significant role in our new economic model.

For this to happen we must grapple with the question at the heart of this compilation: Is the production cooperative an appropriate form of the organisation of labour for a society committed to building socialism? There is no doubt that this question cannot be answered in a simplistic or absolute fashion. Our aim here is to take only a first step towards answering this question from a Cuban perspective in these times of change and rethinking, guided by the anxieties and hopes that many Cubans have about our future.

When it is proposed that the production cooperative be one – though not the only – form of enterprise in Cuba, three concerns above all are frequently encountered: some consider it too “utopian” and therefore inefficient; others, on the basis of the cooperatives that have existed in Cuba, suspect that they will not have sufficient autonomy[1] or that they will be “too much like state enterprises”; while others still, accustomed to the control over enterprise activities exercised by a state that intervenes directly and excessively in enterprise management, reject cooperativism as too autonomous and therefore a “seed of capitalism”. This book tries to take account of all these concerns, though there is no doubt that more space would be required to address them adequately.

The first concern is addressed to some extent with the data provided in the first part of the book regarding the existence and economic activity of cooperatives worldwide today. This shows that the cooperative is not an unachievable fantasy that disregards the objective and subjective requirements of viable economic activity. Thus, the experiences of cooperatives in the Basque Country, Uruguay, Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela that are summarised in the third part of the book demonstrate that cooperatives can be more efficient than capitalist enterprises, even on the basis of the hegemonic capitalist conception of efficiency that ignores externalities, i.e. the impact of any enterprise activity on third parties.

The efficiency of cooperatives is greater still if we take into consideration all of the positive outcomes inherent in their management model, which can be summarised as the full human development[2] of its members and, potentially, of local communities. The democratic abilities and attitudes that cooperative members develop through their participation in its management can be utilised in other social spaces and organisations. Moreover, genuine cooperatives free us from some of the worst of the negative externalities (dismissals, environmental contamination, loss of ethical values) generated by enterprises oriented towards profit maximisation rather than the satisfaction of the needs of their workers.

Jan

By Cliff DuRand

Cuba is engaged in a fundamental reshaping of its society. Calling it a renovation of socialism or a renewal of socialism, the country is re-forming the economic system away from the state socialist model adopted in the 1970s toward something quite new. This is not the first time Cuba has undertaken significant changes, but this promises to be deeper than previous efforts, moving away from that statist model. Fidel confessed in 2005 that “among the many errors that we committed, the most serious error was believing that someone knew how to build socialism.” That someone, of course, was the Soviet Union. So, Cuba is still trying to figure out for itself how to build socialism.

To understand the current renovation it is important to distinguish between ownership and possession of property. The productive resources of society are to remain under state ownership in the name of all the people. Reforms do not change the ownership system. Reforms are changing the management system, bringing managerial control closer to those who actually possess property. So while the state will continue to own, greater autonomy will be given to those who possess that property. In effect, Cuba is embracing the principle of subsidiarity, which holds that decisions should be made at the lowest level feasible and higher levels should give support to the local. This means more enterprise autonomy in state enterprises and it means cooperatives outside of the state.

It is expected that in the next couple years the non-state sector is expected to provide 35% of the employment. Along with foreign and joint ventures, the non-state sector as a whole will contribute an estimated 45% of the gross domestic product (PIB). Hopefully coops will become a dominant part of that non-state sector.

Cooperatives

Already 83% of agricultural land is in coops. Much of that has been in the UBPCs (Basic Units of Cooperative Production) formed in the 1990s out of the former state farms. But these were not true cooperatives since they still came under the control of state entities. Now they are being given the autonomy to become true coops.

Even more significantly, new urban coops are being established in services and industry. 222 experimental urban coops are to be opened in 2013. As of 1st of July, 124 have been formed in agricultural markets, construction, and transportation. A big expansion in this number is expected in 2014.

In December 2012 the National Assembly passed an urban coop law that establishes the legal basis for these new coops. Here are some of its main provisions:

This is a big step forward for Cuba. Since 1968 the state has sought to run everything from restaurants to barber shops and taxis. Some were done well, many were not. One problem was worker motivation. Decisions were made higher up and as state employees, workers enjoyed job security even with poor performance. However, their pay was low. Now as socios in cooperatives they will have incentives to make the business a success. The coop is on its own to either prosper or go under. Each member’s income and security depends on the collective. And each has the same voting right in the General Assembly where coop policy is to be made. Coops combine material and moral incentives, linking individual interest with a collective interest. Each socio prospers only if all prosper.

By JERRY HARRIS

Race and Class

Abstract: The Russian invasion of the Ukraine is a powerful assertion of geopolitical power and conflict. But Russia’s nationalist and expansionary drive takes place within the context of transnational economic ties. Such ties help define the nature of the war, and both the Russian and western response. The contradictory pressures of nationalist desires conflicting with transnational integration is an underappreciated complexity of the war that this article will explore.

Keywords: energy resources, finance capital, nationalism, oligarchy, Russian invasion, sanctions, transnational capitalist class, Ukraine.

Introduction

The invasion of Ukraine is seen by most as a geopolitical conflict between the West and Russia. Nationalist ideologies and power competition do play a significant role, but such competition takes place within the context of transnational relations that also define the nature of the struggle. Unlike the invasion of Czechoslovakia, which took place during limited economic and cultural ties between the West and Soviet Union, the current war is deeply affected by mutual economic relationships between transnational capitalists and links between transnational corporations. Exploring how the contradictions between national and transnational elements structure the character of the war is the purpose of this article.

Global capitalism has gone through tremendous change over the past forty years, building a system of transnational integration characterised by global financial flows and production. This has profoundly changed a world built around nation-centric power. The emergence of the transnational capitalist class (TCC) reshaped domestic economies and social relations by restructuring state institutions and rules to serve the new forms of global accumulation. Major trade arrangements were ratified, banks bailed out, corporate taxes cut, transnational corporations promoted and social contracts undermined. And yet the old forms of power, habits, identities and privileges still fight to maintain their existence. This mixture of national structures overturned by transnational forces creates a powerful vortex of tensions.

In Russia, this process took place first under Yeltsin and then Putin, turning the country into a neoliberal state. As the new ruling class sought a capitalist identity outside the Soviet experience, it linked to its imperial past. As a result, Russian national concepts of power rooted in Tsarist imperialist expansion reasserted their influence, even as the oligarchy made use of transnational accumulation. Neither did Great Power concepts fully fade in the West, as NATO’s eastward expansion shows. As globalisation entered a sustained period of economic, environmental and social turmoil, transnational hegemony was opened to greater challenge, particularly from authoritarian state capitalism, which finds inspiration in fascism and empire. As the globalist project of a fully integrated economic world floundered under the weight of its own excess, nationalist ideology and power projections re-emerged.

Mike Davis hits home when he describes the Putin government as one that hates Lenin and the Bolshevik position on self-determination, a government drenched in Great Russian chauvinism and supported by the reactionary religious hierarchy of the Eastern Orthodox Church. A government that invites the backing of pan-Slavic neo-fascists, that idealises the Tsarist empire, with Putin himself an iconic hero of far-right nationalists throughout Europe and the US.[1]

And yet it is a government that has structured its economy to serve and benefit from transnational capitalism. That contradiction, between nationalist ideology and its transnational model of accumulation, is the Russian trap. And it works both ways, for Russia and for its global partners.

Global Capitalism and Russia

In Russia, the creation of a TCC took place primarily through the privatisation of state assets, in combination with private/state ownership arrangements in energy and finance. The state did not represent a national capitalist class, nor was its primary concern building a modern industrial base. Rather, the state played a central role in integrating the key sectors of the Russian economy into global capitalism. Russian oligarchs also rushed to integrate into elite cultural and financial networks. They sent billions into offshore havens, spent hundreds of millions on London and New York real estate, lived on their yachts, and sent their children to elite western schools.

But the full political integration of the Russian state was stymied by the western architecture of power. NATO’s expansion eastward clashed with Russia’s intent to re-establish its own sphere of influence. This was an uneven process, unfolding over a period of three decades. The G7 became the G8 as Russia was given a seat at the elite table. But tensions never fully resolved. Political, social and environmental problems continued to sharpen, giving rise to security concerns and a renewal of nationalist rhetoric to regain state legitimacy. In turn, rivalries became more aggressive, and the balance between globalism and nationalism began to shift.

To explore the above process, we begin with Russia’s internal transformation and the creation of its transnational capitalist class.

Scholar Oleg Komolov describes the Russian economy primarily as a supplier of resources, with the TCC deeply integrated into global capitalism. He points out how the ruling class that emerged from the privatisation of state assets occupies primarily the role of an intermediate seller of Russian commodities on world markets and is not interested in improving the efficiency of the economy, developing competitive manufacturing industries and technological progress. [Moreover] the export economy was developed with large-scale participation of foreign capital in all sectors of the economy, the artificial devaluation of the ruble and net capital outflow to countries of the center.[2]

Between 1997 and 2017, the outflow of capital exceeded inflows, with offshore havens the destination for 70 per cent of capital exports. The two most prominent outflow years were during the global crash of 2008 and the Russian seizure of Crimea in 2014, with a combined total of $285 billion.[3] Outside the flight to offshore havens, Russian energy TNCs had made foreign direct investments of $335.7 billion by 2017.[4]

The Russian state and private oligarchy worked together in the outflow of capital, which reduces the amount of held dollars and keeps the value of the rouble low. In turn, this helps the export of fossil fuels and minerals. According to the World Bank, the rouble is one of the world’s most undervalued currencies.[5] Oil and gas make up 65 per cent of Russian exports, but minerals and wheat also play an important role. The state has supported this process by increasing its overseas holdings in US Treasury bonds from $8 billion to $164 billion between 2007 and 2013.[6]

Keeping the value of the rouble low meant undercutting investments in the modernization of manufacturing. The results being high import prices for machinery and agricultural inputs, as well as high consumer prices for foreign goods. In 2017, machinery and equipment made up 47 percent of imports, and chemical products 18 percent.[7] Thus, a low-valued rouble drove up the cost of tractors, combines, transport and machine tools, fertilizers and chemicals – a typical pattern among transnational petro-states. Privileging globalist accumulation over the national market marked the Russian ruling class with a transnational character and strategy.

Another aspect of Russia’s integration was creating an attractive market for foreign speculative capital. During the 2005–08 financial frenzy, capital flowed into Russia, benefiting from liberalisation of currency regulations. During these years, transnational capitalists sank $325 billion into Russian corporations, with large amounts going to state-owned entities like Sberbank and the energy giant Gazprom. Among the biggest investors were financial giants JPMorgan, BlackRock and Pimco.[8] Loans were also made, reaching $400 billion from some of the biggest global banks including Citigroup, HSBC, BNP Paribas and Deutsche Bank. The benefits for finance capital were double: debt from loans and earnings from investments meant profits for transnational investors the world over. The outflow of profits over a twenty-year period reached $1.2 trillion, and taking on foreign liabilities certainly didn’t support the rouble.

Energy, transnational capital and sanctions

Key to the Russian economy, and indeed the world economy, are energy resources. Russia’s fossil fuel industry has been largely exempt from the sanctions in 2022, as it was in 2014. In both cases, transfer payments for energy continued to flow through the SWIFT computers, and in 2022 these were worth about $350 million per day. Between 24 February and 24 March 2022, Russia sold $19 billion in fossil fuels. The links between western oil majors and Russian TNCs deeply influences the limits and impacts of sanctions, and so deserves attention.

First, we can review the degree of joint ventures between Russian and transnational energy majors. Rosneft emerged as Russia’s largest oil producer when Putin dismantled Yukos, and sold its $90 billion in assets for just $2 billion. Western banks rushed to loan Rosneft $22 billion as it became Russia’s dominant energy company. Financial backing came from ABN Amro, Barclays, BNP Paribas, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan and Morgan Stanley. Rosneft then raised $10.7 billion in an IPO on the London Stock Exchange with BP taking a 20 per cent stake. Other strategic investors included Petronas (Malaysia) and CNPC (China). Russian oligarchs joined in, with Roman Abramovich, Vladimir Lisin and Oleg Deripaska each investing $1 billion. As Hans-Joerg Rudloff, chairman of Barclays and Rosneft board member, noted, Russia was ‘on the track of international economic integration’.[9] In 2006 Rosneft turned east, joining with China’s Sinopec in a $13.7 billion buyout of TNK-BP’s Udmurtneft Oil. In a key deal after the 2014 imposition of sanctions, Rosneft signed a thirty-year contract with the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation worth about $400 billion. Furthermore, Exxon had a $3.2 billion Arctic offshore drilling deal with Rosneft in which the Russian TNC obtained minority stakes in the Gulf of Mexico and oil fields in Texas. Rex Tillerson, chief executive of Exxon Mobile and future Secretary of State, received the Order of Friendship award from Putin in gratitude for Exxon’s commitment.[10]

Gazprom also has a significant level of transnational integration. In developing Shtokman, one of the world’s largest gas fields, Gazprom partnered with Total from France and StatoilHydro of Norway. Total has a close relationship with the Russians. The French oil major has investments in two other Russian oil fields, and a 16 per cent stake in Novatek, the country’s largest gas producer after Gazprom. The largest foreign investment project in Russia, the Sakhalin-2 oil field, involved the British and Japanese. Although Gazprom retains majority ownership, Shell held 27.5 per cent, Mitsui 15 per cent, and Mitsubishi 10 per cent.[11]

Overall, more than 400 foreign financial institutions have provided $130 billion to Russian energy companies, $52 billion in investments and $84 billion in credit. A total of 154 US financial companies hold almost half of these investments at $23.6 billion. JPMorgan is the largest with investments and loans of $10 billion. Other major investors include Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund with $15.3 billion invested in Rosneft. The UK was the third largest investor, where 32 financial institutions contributed $2.5 billion. Other important investors come from Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, Japan and China.[12]

To understand how sanctions disrupted these transnational relations, we need to investigate sanctions from 2014 and 2022. In 2014, companies weren’t banned from conducting business with Russian state-owned energy giants, although banks were sanctioned from making loans. The policy allowed protection for transnational institutional investors. But the US did move to sanction Rosneft’s president, Igor Sechin. This prompted Jack Ma, founder of China’s Alibaba, and John J. Mack of Morgan Stanley, to resign from the Rosneft board; while Donald Humphreys, former chief financial officer of Exxon Mobil, and BP chief executive Bob Dudley continued to serve. As western sanctions tightened, they did cause some difficult problems, forcing Eni, Exxon and Statoil to withdraw from a $20 billion Rosneft Arctic exploration project. But to replace the loss of advance drilling technology, Rosneft took a 30 per cent stake in North Atlantic Drilling, a subsidiary of Seadrill, the world’s largest offshore driller controlled by Norway’s richest man, John Fredriksen. Rosneft also faced problems when sanctions cut access to foreign capital markets. To counteract the sanctions, it arranged a series of prepayment deals with some of the largest western oil traders including Glencore, Trafigura and BP. Furthermore, Rosneft bought Morgan Stanley’s global oil trading business, obtaining an international network of oil tank storage contracts, supply agreements and freight shipping contracts, as well as a 49 per cent stake in Heidmar, a manager of oil tankers. So, while the 2014 sanctions caused a number of real problems, Rosneft’s transnational relationships provided important avenues to avoid major disruptions.[13]

Overall, the 2014 sanctions did hurt Russia. FDI inflows fell from $69 billion in 2013 to $21 billion in 2014. But the Obama administration also faced stiff resistance not only across Europe, but in the US as well. Hostility to the sanctions came from the two most influential US business groups, the National Association of Manufacturers and the US Chamber of Commerce. Both lobbied and took out critical ads in national newspapers, insisting that sanctions should not hurt financial institutions that held significant Russian debt. Among the corporations who lobbied against the sanctions were Exxon Mobil, BP, American Petroleum Institute, Amway, Caterpillar, Chevron and GM.[14]

In implementing sanctions, the US believed Russia would view its global business ties as too valuable to lose, and so economic pressure would force a retreat from eastern Ukraine. But from the other side of the mirror, Putin believed global business’s ties to Russia were too valuable and would undercut western sanctions. In important ways both were right, and the same dynamic is at play in 2022. In the recent crisis the US Chamber of Commerce has again lobbied Congress arguing sanctions should be ‘as targeted as possible in order to limit potential harm to the competitiveness of U.S. companies’.[15]

The magnitude of the 2022 invasion has caused the current sanctions to be deeper and broader. What Russian Marxist Boris Kagarlitsky pointed out in 2014 is even more true today:

The situation confronting our elites … is more or less straightforward, they cannot enter actively into confrontation with the West without dealing crushing blows to their own interests, to their own capital holdings and to their own networks, methods of rule and way of life.[16]

But this is a two-way street – the West can’t sanction Russia without hurting itself, so the question becomes who hurts the most. For example, the world’s largest asset manager BlackRock took a loss of $17 billion on their Russian exposure.[17]

Because Russia is the main supplier of oil and gas to Europe, its energy industry is a major focus of new sanctions. ExxonMobil is beginning steps to exit the Sakhalin-1 project and cease operations it carries out on behalf of a consortium of Japanese, Indian and Russian companies. Shell also announced plans to leave Sakhalin and ‘withdraw all involvement in Russian hydrocarbons’.[18] BP has moved to offload its 20 per cent stake in Rosneft and may take a hit estimated at $25 billion. BP’s move comes after thirty years of joint venture. Additionally, the Singapore-based trading company Trafigura is threatening to opt out of its 10 per cent shareholding of Vostok Oil, a vast gas project led by Rosneft. And Norway’s Equinor will also begin to exit its joint ventures. But TotalEnergies, the large French transnational, while committing to no new investments, is holding on to its nearly 20 per cent of Novatek.

Yet none of these companies may end up leaving. Exxon, BP and Shell need to find someone to buy out their interests. That will not be easy in the present circumstances, and they may have to appeal to their Russian counterparts to take their shares. Furthermore, oil tankers continue to transport millions of barrels of oil from Russian ports, estimated to be worth $700 million per day. These include tankers from Greece, and those chartered by US oil giant Chevron.[19] And SWIFT payment transfers for energy continue at the above-mentioned $350 million per day. Consequently, for all the difficulties of the sanctions, global energy integration affords Russia significant amounts of capital, which helps to finance the war.

India’s case is yet another example of the complexity of transnational production. Obtaining about a 33 per cent discount from Russia, India’s oil imports have surged by 700 per cent.[20] Some of these imports go to Reliance Industries, which has the world’s largest refinery complex, and also to an affiliate of Rosneft, Nayara Energy. Using Russian crude, Indian refineries produce diesel and jet fuel, which is sold to Europe, whose imports from India have jumped. As Shell’s chief executive explained, oil substantially treated or changed loses it national origin. ‘We do not have systems in the world to trace back whether that particular molecule originated from a geological formation in Russia, [therefore] diesel going out of an Indian refinery that was fed with Russian crude is considered to be Indian diesel.’[21]

One particularly ironic aspect of transnational relations is that Russian gas flows through pipelines running through Ukraine to Italy, Austria and eastern Europe. Russia pays transport fees to the government, thus supplying funds to Ukraine even as the war raged. And, of course, gas reaching the EU means more money for Russia. It wasn’t until May 2022 that Ukraine stopped the Sokhranovka pipeline that operates from the Russian-controlled Luhansk region. The value of the gas is about $1 billion each month. But Sudzha, Russia’s main pipeline, is, at the time of writing, still in Ukrainian-held territory, allowed to operate, and expected to take on some of the lost capacity.

Another example of the complexity of transnational production is how the invasion impacted Rusal, the world’s second-largest aluminium producer, owned by Oleg Deripaska and listed on the Hong Kong market. Rusal has a joint venture with Australian mining giant Rio Tinto. But because of sanctions, their joint refinery, Queensland Alumina, will not ship products to Russia. The result is that Rusal had to halt production at its Nikolaev refinery located in Ukraine, which accounts for 23 per cent of its annual production. Nikolaev is one of the most modern refineries in the world and employs about 1,500 people. To make up the shortfall Rusal may divert production from its Aughinish refinery in Ireland to feed its Russian smelters.[22] In turn, that will reduce supplies in Europe where materials are already short. The end result is higher unemployment in Ukraine, higher prices in Europe, and a lower stock price for Rusal.

Data compiled by the Yale School of Management reported 253 TNCs are making a clean break with Russia, essentially leaving no operations behind. Some of these include Uber, Shell, Salesforce, Reebok, McKinsey, Nasdaq, eBay, Delta, Deloitte, BP, BlackRock, American Airlines and Alcoa. Another 248 companies have suspended their operations without permanently exiting or divesting. Among these are Adidas, American Express, Burger King, Chanel, Coca-Cola, Dell, Disney, GM, Hewlett Packard, Honeywell, Hyundai, IBM, McDonalds, Mastercard, Nike, Oracle, Starbucks, UPS, Visa and Xerox. Some seventy-five companies have suspended a significant portion of their business. These include Caterpillar, John Deere, Dow, GE, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Kellogg’s, Pepsico and Whirlpool. Pausing new investments are ninety-six companies. This is different from JPMorgan and Goldman Sachs who, while suspending some operations, continue to snatch up depressed Russian securities at very low prices. Among those pausing new investments are Cargill, Colgate-Palmolive, Credit Suisse, Danone, Johnson & Johnson, Siemens and Unilever. The total so far is 672 companies taking various forms of action. Yale reported 162 companies staying the course, including Acer, Alibaba, International Paper, Koch, and Lenovo.[23]

Some funds not appearing in the Yale report include the important financial centres in Singapore, which has halted any new economic activity with four major Russian banks. And Singapore’s large sovereign wealth funds, which have about $6 billion invested in Russia, have also suspended activity.[24] Two of China’s largest state-owned banks are limiting loans for purchases of Russian commodities.[25] The New Development Bank, established by Russia, China, Brazil and South Africa, put new transactions on hold. And the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, whose major shareholder is China, stopped its projects in Russia and Belarus. As of the middle of March 2022, there were more than 3,600 sanctions on Russian individuals and companies.

Table 1: Estimated and potential losses of companies leaving Russia[26]

| Companies Leaving Russia | Estimated and Potential Loss (US$ million) |

| BlackRock | $17,000 |

| Bank of America | $700 |

| BNY Mellon | $200 |

| Citigroup | $1,900 |

| Ericsson | $95 |

| Goldman Sachs | $300 |

| JPMorgan | $1,000 |

| Nokia | $109 |

| Shell | $5,000 |

| Société Générale | $3,300 |

| Volvo | $423 |

The rush to boycott Russia reminds one of the corporate rush to endorse Black Lives Matter; essentially a marketing strategy to stay in front of popular politics. And while the costs are disruptive, transnational corporations are large enough to swallow such losses. For example, as the price for oil rose, Shell increased its early quarterly profits by 300 per cent to $9.1 billion – already enough to cover its projected $5 billion loss. Most of these sanctions will only harm the Russian people without having any real effect on the ruling class or the invasion. Russian citizens are already experiencing a dramatic decline in purchasing power and may soon face growing unemployment and a lack of consumer goods. The larger developing crisis is in world food supplies as Russia and Ukraine export a significant amount of the world’s wheat, corn, barley and sunflower oil. Shortages and price increases will hit the poor in the Global South the hardest.

Financial institutions and the TCC

Because of the integration of the global financial system, Russian capital was exposed to severe sanctions in 2022 that constituted a geo-economic break. There has been a general belief in the sanctity of foreign reserves. The US often talks about a ‘rules-based world order’. This includes open capital markets and accounts, deeply integrated financial markets, and benchmark assets in US dollars. Putin counted on all of this to keep the Russian economy functioning during the invasion. But seven of the largest Russian banks have been removed from the SWIFT interbank system. This severely limits the ability to pay for imports or receive payment for exports, as SWIFT is used to link funds for transnational deals. Russia’s central bank also kept about half its $630 billion dollars and euro reserves in foreign institutions residing in London, New York, Paris and Tokyo, and from $86 to $140 billion in Chinese bonds. Except for the Chinese holdings, these funds are now frozen, causing the rouble to lose about 40 per cent of its value, although with capital controls the rouble regained most of its value. Moreover, the collapse of Russian corporate stocks triggered the multi-week closure of the Russian stock market. And both Moody and Fitch downgraded Russian sovereign debt to ‘junk’. Russia is moving towards its first foreign currency debt default in one hundred years, but, as of May 2022, was still making payments using money from energy exports.

The severity of the economic sanctions is a radical step. Even during the second world war, relations between the Bank of England and the Reichsbank continued into the 1940s. And the Bank of International Settlements continued to allow the German central bank access to its clearing and settlement facilities throughout the war.

As Dominik Leusder points out:

More than any armed conflict, the current international monetary system has laid bare the folly of this romantic liberal portrait of globalisation. The sanctions against Russia are the clearest manifestation yet of a distinct undercurrent of financial globalisation … the West’s ability to coerce states has only increased as a function of their integration [so] as Russia became a central node [of] the global economy, it became more vulnerable.[27]

And yet western investors and companies are also in danger, as sanctions over the transfer of funds may mean Russia defaults on billions in loans. Facing such problems, US authorities gave the okay to JPMorgan to process interest payments due on dollar bonds from the Russian government. Citigroup is another payment agent for about fifty corporate bonds tied to Russian TNCs like Gazprom and MMC Norilsk Nickel. [28] Furthermore, the important financial institution Gazprombank is spared from sanctions and continues to be a conduit for commodity transactions. For example, working with Citibank it helped Brazil purchase Russian fertiliser, which is not sanctioned. Thus, the flow of capital continues, at least in part, despite sanctions.

Again, Leusder provides insightful analysis:

As globalization underwrote Putin’s militarism and his increasingly hostile posture toward Russia’s neighbors, it simultaneously rendered the country’s economy fatally reliant: on the net demand from other countries such as Germany and China; on imports of crucial goods such as machinery, transportation equipment, pharmaceutical and electronics, mostly from Europe; on access to the global dollar system to finance and conduct trade … This is one way to construe the deceptively simple insight of Henry Farrell and Abraham L. Newman’s theory of weaponized interdependence: the logic of financial globalization that generated Russia’s trade surplus and gave Putin room to maneuver also provided the economic and financial weaponry that was turned against him.[29]

Thus, a nationalist strategy to reconstitute the Russian empire, using the profits and ties that come with globalisation, is undercut by the contradiction of those same ties and relationships.

Weaponised interdependence is a good description of the financial markets in metals. Alongside Russian fossil fuels are its exports of metals, including copper, alumina and nickel, which is used in making stainless steel and batteries for electric cars. Here are the complications of transnational capitalism. Tsingshan Holding Group in China is the world’s largest nickel producer, China’s second largest steel producer, and is involved in electric vehicle batteries. Tsingshan made an enormous $3 billion bet shorting the price of nickel, counting on its own increased production in creating an abundance of supplies. This bet was made on the London Metal Exchange (LME), which is a unit of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited. With the Russian invasion, although nickel was not sanctioned, fear took hold of the market and prices jumped 250 per cent. The short bet based on lowering cost was a disaster. Trade chaos took hold, leaving Tsingshan with two choices. Either deliver tons of nickel or pay for margin calls, which means coming up with the cash or securities to cover potential losses. But Tsingshan only held 30,000 tons of its 150,000-ton bet. The remainder was held by JPMorgan, BNP Paribas, Standard Chartered and United Overseas Bank. On the cusp of a global financial disaster, LME suspended trading and retroactively cancelled $3.9 billion of trades, blaming banks for preventing efforts to create greater transparency that could have revealed the interconnected problem.[30] Consequently, the Russian invasion set off a financial crisis that punished transnational capitalists that have no part in the war.

Facing sanctions, oligarchs can’t be happy with the war, and a number have stated their opposition. Nevertheless, the global financial system has been built to safely hide their money, as well as the wealth of others in the TCC. It’s estimated that oligarchs have hidden about half their wealth offshore, amounting to some $200 billion. Somewhere between 10,000 to 20,000 Russians hold more than $10 million each in offshore assets and havens.[31] Still, that is significantly less than their American counterparts who have an estimated $1.2 trillion in offshore tax havens. Much of the Russian money is in US, UK and EU assets. Transparency International has estimated about $2 billion just in UK property.[32]

But much of this wealth is difficult to discover because the TCC has structured international laws to hide wealth in complex trusts and shell corporations.[33] Global accounting firms PwC, KPMG, Deloitte and EY helped oligarchs move money to offshore shell companies for years before currently withdrawing services. Rosneft, VTB, Alfa Bank, Gazprom and Sberbank have been represented by leading US law firms, including White & Case, DLA Piper, Dechert, Latham & Watkins and Baker Botts. And Baker McKenzie, one of the world’s largest law firms, continues to represent some of Russia’s largest companies, including Gazprom and VTB.[34] Concord Management specialised in serving ultra-wealthy Russians, helping them invest in hedge funds, private equity and real estate. Since 1999, Concord has channelled billions to BlackRock, Carlyle Group and others. Wall Street banks such as Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley often acted as intermediators, linking Concord to hedge funds.[35] Such well-worn networks tie the Russian TCC to global capitalists and financial institutions in a mutually beneficial relationship, and creates a shared culture that exalts the privileges of wealth and common ideas about how the world economic system works.

Capitalists the world over make use of sophisticated accountants, bankers and lawyers to hide their assets. An agent will set up an offshore shell company in a country with little transparency. This company then creates more shells in other low-transparency jurisdictions – about forty-two exist across the world, including the US states of Delaware and South Dakota. This allows the ‘ultimate beneficial owner’, often unknown, to have multiple bank accounts and the ability to move money and invest without any scrutiny. Government investigators in both the US and the UK regularly ignore suspicious banking activity. In 2018, the EU passed regulations demanding access to information on the ownership of European companies nested in shell companies. Yet in 2022 no such registry exists. Congress passed a transparency law in 2021 with a $63 million budget, but never provided the money to the Treasury Department. Consequently, the effort to sanction oligarchs is undercut by the global financial system built to the demands of the TCC, of which Russian capitalists are members. While some pressure is being directed on the oligarchs, the system of hidden cross-border capital flows is too valuable to end, allowing the Russian TCC to escape greater harm.

A good example of how shell corporations function is the effort to sanction Arcady Rotenberg. Rotenberg is worth about $3 billion with an estimated $91 million invested in the US and a $35 million mansion outside London, bought through an entity in the British Virgin Islands. He has at least 200 companies located across dozens of countries. Even after coming under sanctions in 2014, Rotenberg became the owner of two additional companies located in Luxembourg, well known as a haven for billionaires. Although senate investigators found countless bank filings on suspicious Rotenberg activities, none of them have been investigated by the Treasury Department.

As Cihan Tuğal reminds us, Putin and his cronies

are a solid part of world capitalism, and their apparently insane actions are intended to produce a better place at the table. They want to be recognized as legitimate imperialists in the new, post-Wilson and post-Lenin world of the 21st century … [Putin] is not only serving his ego, but a capitalist class fostered by post-1991 reforms, which were selective appropriations of free market ideas. The gang of cronies is not Putin’s creation alone. It is an outcome of transnational dynamics. This class is hungry for markets, and it cannot help but look for ways to burst out of Russia.[36]

German/Russian economic relations

Moving from a picture of transnational markets, industries and finance, we can explore the specific relationship between Germany and Russia. Germany as the largest European economy is also the most integrated with Russia. For Russia, it’s their most important economic partner alongside China. In 2021, German exports to Russia were worth more than $28.4 billion, and it invested a further €25 billion in operations.[37] Germany still depends on Russia for about 55 per cent of its natural gas, 35 per cent of its oil, and half its coal.

Before 2014, there were 7,000 German companies inside Russia representing some of the largest TNCs in the world, such as Adidas, BASF, Siemens, Volkswagen, Opel and Daimler. On the financial side, all major German commercial banks were active in Russia. In terms of oil and gas, Germany’s biggest energy group Eon was the largest foreign shareholder in Gazprom, which, alongside BASF, was building the $6.6 billion Baltic Sea pipeline. The Germans held 20 per cent of the Nord Stream joint venture, with former chancellor Gerhard Schröder as chairman and Matthias Warnig of Dresdner Bank its chief executive. Even after the seizure of Crimea, Siemens CEO Joe Kaeser confirmed its commitment to Russia to sell trains, energy infrastructure, medical technology and manufacturing automation technology. Cross-border deals also continued, with RWE selling its oil and gas subsidiary to Russia’s LetterOne for over $7.5 billion. But, with the 2014 sanctions, German trade with Russia dropped by 35 per cent, and German firms investing in Russia dropped to just under 4,000 by 2020.[38]

Now the invasion of Ukraine has shaken the German/Russian relationship in a very significant manner, particularly in the auto and energy industries. Wintershall Dea, an oil and gas TNC, will stop payments to Russia and write off its €1 billion investment in Nord Stream 2. Additionally, it will not receive revenues from its Russian operations, which accounted for about 20 per cent of its 2021 profits. The company issued a statement on the turmoil caused by the invasion lamenting,

What is happening now is shaking the very foundations of our cooperation. We have been working in Russia for over 30 years … We have built many personal relationships – including in our joint ventures with Gazprom. But the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine marks a turning point.[39]

Nord Stream 2 has been a contentious issue between the US and Germany for years. The pipeline running through the Baltic goes directly to Germany. The US has pressured Germany to end the project, but Angela Merkel refused to do so. The project, worth $11 billion, is registered as a Swiss firm whose parent company is Gazprom. Gazprom owns the pipeline and paid half the costs, the rest shared by Shell, Austria’s OMV, France’s Engie, and Germany’s Uniper and Wintershall DEA.[40] The invasion has prompted Germany to halt the project. The suspension of Nord Stream 2 may not be permanent, but even a temporary suspension is a huge shift.

Russia exports fifty-six billion cubic metres of liquefied natural gas to Germany yearly. Inside Germany, Gazprom owns and operates thousands of miles of pipeline, key storage facilities, and the largest underground storage tank for natural gas in western Europe. Russia also supplies German refineries with a third of their oil, a number with long-term contracts that Russia is not willing to cancel. Particularly ironic are the weapons sent by the German government to Ukraine that use steel produced in German factories powered by coal coming from Russia. As Putin has stated:

Let German citizens open their purses, have a look inside and ask themselves whether they are ready to pay three to five times more for electricity, for gas and for heating … You can’t isolate a country like Russia in the long run, neither politically nor economically. German industry needs the raw materials that Russia has. It’s not just oil and gas, it’s also rare earths. And these are raw materials that cannot simply be substituted.[41]

Turmoil has also hit the auto industry. Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz and BMW halted production in Russia, and also suspended all vehicle exports. But the invasion has had an even bigger impact because of the coordination of production between Ukraine and European auto companies. With its low labour costs and educated workforce, Ukraine became a manufacturing centre of systems which connect electronic components, like tail lights and car entertainment systems. The work, done by hand, requires a large number of skilled workers. The fighting brought production to a sudden halt, and within days the lack of parts shut down European factories. BMW shut several plants in Germany, Austria and Britain, while VW was brought to a standstill at multiple locations, including its main site in Wolfsburg. Electric vehicle production at Zwickau stopped, including its SUV exports to the US, and Porsche idled manufacturing the Cayenne sport utility vehicle in Leipzig. As Jack Ewing noted:

No car can operate without wiring systems, which are often tailor-made to specific vehicles. So-called wiring harnesses are among the first components to be installed in a new vehicle, and their absence brings assembly lines to a standstill.[42]

Furthermore, Ukraine is also a major source of neon, a gas used for high-performance lasers required for production of scarce semiconductors, adding more woes to the industry.

None of these economic disruptions are welcomed by the TCC. But the German government has taken a major step away from its previous positions. At first opposed to banning Russia from SWIFT, and refusing to send arms to Ukraine, it has now reversed on both those issues. And the sizeable increase in its military budget surprised everyone. Although transnational links are deep, for now geopolitical tensions are riding roughshod over economic concerns. But such concerns have not gone away. The New York Times observes that ‘multiple cracks’ have already occurred over ‘lost trade, higher energy prices, slimmer profits and lower economic growth’, as well as lower employment.[43] As Martin Brudermüller, the chief executive of the chemical giant BASF stated, ‘Cheap Russian energy has been the basis of our industry’s competitiveness’.[44] And again, ‘Do we want to blindly destroy our entire national economy? What we have built up over decades?’[45] What is true for BASF is true for the German economy, whose success is built upon cheap gas from Russia and exports to China.

Conclusion

There are a number of questions not explored in this article. NATO’s eastward expansion, Great Russian chauvinism, fascist forces in both Russia and Ukraine, the meaning of independence and self-determination, US hypocrisy on foreign interventions, China’s role, and growing debates within the Left over the war. All these topics already have a growing and substantial body of literature. Also, events continue to rapidly develop and so the article has some time limitations. But the deeper issues on the intersections between national geopolitics and transnational economics, and how the resulting contradictions affect the war, will continue. What is clearly evident is that global capitalism has plunged the world into yet another crisis. A crisis that ignores a pandemic that threatens the health of every human on the planet, and an environmental crisis that threatens every species. The failure is staggering in its ignorance.

What the new global configuration will look like is difficult to tell. Much depends on how the conflict ends. A long-term occupation will freeze Russia’s transnational links, a rapid conclusion may mean the easing of sanctions. The invasion is a further deconstruction of the global capitalist system built over the past forty years of neoliberal hegemony. But there are still many trillions of dollars in cross-border accumulation, and global assembly lines continue to churn out commodities in a coordinated system of production and trade. The current problems in logistics and supplies are not because of too little demand, but because of too much, with the infrastructure of ports, shipping and transportation actually too limited. Such problems might call for an expansion of globalisation, which is at the heart of China’s Belt and Road strategy. But economic, political and social disruptions cause states to look to their own national security. As a result, the contradictions between national and transnational forces continue to be the nexus for world events, changing the balance of forces into new configurations of struggle.

This complex relationship between nationalism and globalism needs to be understood through historical materialism, which defines the world as a continual process of movement. Marx saw everything in motion – production, distribution, environmental metabolic relationships, the class struggle, and all human interactions. Change was driven by the balance between opposing forces, and the results were defined by the power between the aspects. How much of the old that remained, and how much of the new that was asserted, continually set the conditions for the movement to continue. This process of motion and change results in contradictions unfolding in many different forms. There is no historic queue in which socialism waits its turn to appear at the front of the line.

In the current capitalist world, neither nation-centric nor transnational relationships exist in isolation from the other. They exist in the same institutions and continually define and determine each other within a changing balance of forces. This unity of opposites in tension and conflict is what produces the historic transformation towards a new synthesis. No outcome is predetermined, but produced by the dynamic itself. Consequently, what aspects of nation-centric relationships survive or re-emerge depend on the agency of political struggle. Under pressure of globalist economic and environmental crisis, nationalist antagonisms have rematerialised, but within the context of transnational relationships. Globalisation didn’t create the ‘end of history’ because the past continues to exist in the present.[46]

We can see this contradiction in the balance between national and transnational forces in the Russian invasion. A balance in which nationalism and inter-state conflict has grown stronger as the forty-year hegemony of neoliberal globalisation has faced a series of economic, environmental and social crises. As the balance of power shifts, aspects of the old system reassert themselves, but deeply affected and redefined by the changes globalisation engendered. Old ideas and conflicts may re-emerge, yet they are never the same, but contextualised through the new forces that have asserted themselves. So, in analysing the Russia/Ukraine/NATO conflict, we must be careful not to place it in the world of the 1960s, but a world deeply restructured by transnational capitalism.

References

Jerry Harris is national secretary of the Global Studies Association of North America. He is the author of over 100 journal and newspaper articles, and his latest book is Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy (Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press, 2016).

[1] M. Davis, ‘Thanatos triumphant’, New Left Review (Sidecar), 7 March 2022.

[2] O. Komolov, ‘Capital outflow and the place of Russia in core-periphery relationships’, World Review of Political Economy 10, no. 3 (2019).

[3] Komolov, ‘Capital outflow’.

[4] UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development), 2017 Foreign Direct Investment: Inward and Outward Flows and Stock, 1970–2016 (NY: UNCTAD, 2017).

[5] World Bank, ‘PPP conversion factor, GDP (LCU per international $)’, 11 October 2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/pa.nus.ppp.

[6] US Department of Treasury, ‘Major foreign holders of Treasury securities (in billions of dollars)’, 9 July 2019, http://ticdata.treasury.gov/Publish/mfh.txt.

[7] Federal Customs Service of the Russian Federation, ‘Foreign trade of the Russian Federation on Goods, Federal Customs Service of the Russian Federation’, 27 November 2018, http://www.customs.ru/index.php?option=com_newsfts&view=category&Itemid=1978.

[8] L. Thomas Jr, ‘Foreign investors in Russia vital to sanctions debate’, The New York Times, 17 March 2014, https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/03/17/foreign-investors-in-russia-vital-to-sanctions-debate/.

[9] S. Wagstyl, ‘Russian boom will end in pain, says banker’, Financial Times,24 April 2007, p. 5.

[10] D. Filipov, ‘What is the Russian Order of Friendship and why does Rex Tillerson have one?’, The Washington Post, 13 December 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/12/13/what-is-the-russian-order-of-friendship-and-why-does-trumps-pick-for-secretary-of-state-have-one/.

[11] C. Chyong and V. Tcherneva, ‘Europe’s vulnerability on Russian gas’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 17 March 2015, http://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_europes_vulnerability_on_russian_gas.

[12] D. Carrington, ‘UK and US Banks Among Biggest Backers of Russian ‘Carbon Bombs”, Data Shows’, The Guardian, 24 August 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/aug/24/uk-and-us-banks-among-biggest-backers-of-russian-carbon-bombs-data-shows.

[13] J. Harris, Global Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy (Atlanta, Clarity Press, 2016).

[14] Open Secrets, ‘Clients lobbying on H.R. 5859: Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014’, https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/bills/summary?cycle=2021&id=hr5859-113.

[15] H. Tabuchi, ‘How Europe got hooked on Russian gas despite Reagan’s warning’, The New York Times, 23 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/23/climate/europe-russia-gas-reagan.html.

[16] B. Kagarlitsky, ‘Crimea annexes Russia’, LINKS International Journal of Socialist Renewal, 9 April 2015, http://links.org.au/node/3790.

[17] Daily Business Briefing, ‘Here’s how much it is costing companies to leave Russia’, The New York Times, 11 April 2022.

[18] S. Reed, ‘The future turns dark for Russia’s oil industry’, The New York Times, 8 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/08/business/russian-oil-industry.html.

[19] H. Tabuchi, ‘Citing a Chevron tanker, Ukraine seeks tougher restrictions at Russian ports,’ The New York Times, 16 March 2022; I. Ouyang, ‘LME nickel mayhem: London to resume trading after Chinese ‘Big Shot’ Tsingshan lines up bank credit to forestall market chaos over its short positions’, South China Morning Post, 15 March 2022, https://www.scmp.com/business/banking-finance/article/3170570/lme-resume-nickel-trading-after-chinese-short-seller; J. Farchy and M. Burton, ‘LME boss says banks are partly to blame for nickel short squeeze’, Bloomberg, 18 March 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-18/lme-boss-says-banks-are-partly-to-blame-for-nickel-short-squeeze.

[20] H. Tabuchi and B. Migliozzi. ‘A tanker’s giant U-turn reveals strains in the market for Russian oil’, 2 April 2022, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/02/climate/oil-tankers-russia.html.

[21] S. Reed, ‘Shell reports a record $9.1 billion profit’, The New York Times, 5 May 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/05/business/shell-earnings-record-profit.html

[22] E. Ng, ‘Ukraine conflict: Hong Kong-listed aluminium giant Rusal’s shares plunge after Australia bans export of key materials to Russia’, South China Morning Post, 21 March 2022, https://www.scmp.com/business/article/3171224/ukraine-conflict-hong-kong-listed-aluminium-giant-rusals-shares-plunge.

[23] J. Sonnenfeld and S. Tian, ‘Some of the biggest brands are leaving Russia. Others just can’t quit Putin. Here’s a list’, The New York Times, 7 April 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2022/04/07/opinion/companies-ukraine-boycott.html.

[24] Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute (SWFI), ‘GIC sovereign wealth fund and Temasek turn their backs to Russia over Ukraine invasion’, 7 March 2022, https://www.swfinstitute.org/news/91630/gic-sovereign-wealth-fund-and-temasek-turns-their-backs-to-russia-over-ukraine-invasion.

[25] Bloomberg, ‘Ukraine crisis: crude oil price soars as sanctions on Russia spur fear of a global energy crisis’, South China Morning Post, 28 February 2022, https://www.scmp.com/business/commodities/article/3168654/ukraine-crisis-crude-oil-price-soars-sanctions-russia-spur.

[26] Daily Business Briefing, ‘Here’s how much it is costing companies to leave Russia’, The New York Times, 11 April 2022.

[27] D. Leusder, ‘The art of monetary war’, 12 March 2022, https://www.nplusonemag.com/online-only/online-only/the-art-of-monetary-war/.

[28] Bloomberg, ‘Russia default averted for now as JPMorgan processes bond payments’, 17 March 2022, https://www.businesslive.co.za/bloomberg/news/2022-03-17-russia-default-averted-for-now-as-jpmorgan-processes-bond-payments/.

[29] D. Leusder, ‘The art of monetary war’.

[30] I. Ouyang, ‘LME nickel mayhem’.

[31] R. Reich, ‘We aren’t going after Russian oligarchs in the right way. Here’s how to do it’, RSN.org, 9 March 2022, https://www.rsn.org/001/we-arent-going-after-russian-oligarchs-in-the-right-way-heres-how-to-do-it.html.

[32] Transparency International UK, ‘Stats Reveal Extent of Suspect Wealth in UK Property and Britain’s Role as Global Money Laundering Hub, 18 February 2022, https://www.transparency.org.uk/uk-money-laundering-stats-russia-suspicious-wealth.

[33] M. Apuzzo and J. Bradley, ‘Oligarchs got richer despite sanctions. Will this time be different?’, The New York Times, 16 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/16/world/europe/russia-oligarchs-sanctions-putin.html.

[34] M. Goldstein, K. P. Vogel, J. Drucker, M. Farrell and M. McIntire, ‘How western firms quietly enabled Russian oligarchs’, The New York Times, 9 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/09/business/russian-oligarchs-money-concord.html.

[35] M. Goldstein and D. Enrich, ‘How one oligarch used shell companies and Wall Street ties to invest in the U.S.’ The New York Times, 21 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/21/business/russia-roman-abramovich-concord.html.

[36] C. Tuğal, ‘Putin’s invasion: imperialism after the epoch of Lenin and Wilson’, LeftEast, 6 March 2020, https://lefteast.org/putins-invasion-imperialism-after-the-epoch-of-lenin-and-wilson/.

[37] M. Eddy, ‘For German firms, ties to Russia are personal, not just financial’, The New York Times, 6 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/06/business/germany-russia-companies.html.

[38] M. Eddy, ‘For German firms’.

[39] M. Eddy, ‘For German firms’.

[40] J. Mason, ‘U.S. slaps sanctions on company building Russia’s Nord Stream 2 pipeline’, Reuters, 23 February 2002, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-plans-sanctions-company-building-russias-nord-stream-2-pipeline-cnn-2022-02-23/.

[41] K. Bennhold, ‘The former Chancellor who became Putin’s man in Germany’, The New York Times, 23 April 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/23/world/europe/schroder-germany-russia-gas-ukraine-war-energy.html.

[42] J. Ewing, ‘Car industry woes show how global conflicts will reshape trade’, The New York Times, 7 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/07/business/cars-russia-china-trade.html.

[43] K. Bennhold and S. Erlanger, ‘Ukraine war pushes Germans to change. They are wavering’, The New York Times, 12 April 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/12/world/europe/germany-russia-ukraine-war.html.

[44] K. Bennhold and S. Erlanger, ‘Ukraine war pushes’.

[45] M. Eddy, ‘Why Germany can’t just pull the plug on Russian energy’, The New York Times, 5 April 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/05/business/germany-russia-oil-gas-coal.html.

[46] J. Harris, Global Capitalism.

Click HERE for a closeup view of the graphic.

By Carl Davidson

Feb. 27, 2022

“If you know the enemy and know yourself, your victory will not stand in doubt; if you know Heaven and know Earth, you may make your victory complete.”

–Sun Tzu, The Art of War

Successful strategic thinking starts with gaining knowledge, in particular gaining adequate knowledge of the big picture, of all the political and economic forces involved (Sun Tzu’s Earth) and what they are thinking, about themselves and others, at any given time. (Sun Tzu’s Heaven). It’s not a one-shot deal. Since both Heaven and Earth are always changing, strategic thinking must always be kept up to date, reassessed and revised.

This statement above was part of the opening to a widely circulated article I wrote four times now, about two, four, six, and eight years ago. With the upcoming November 2022 elections, it’s time to take my own advice again and do another update. The electoral strategic terrain is constantly changing, and we don’t want to be stuck with old maps and faulty models.

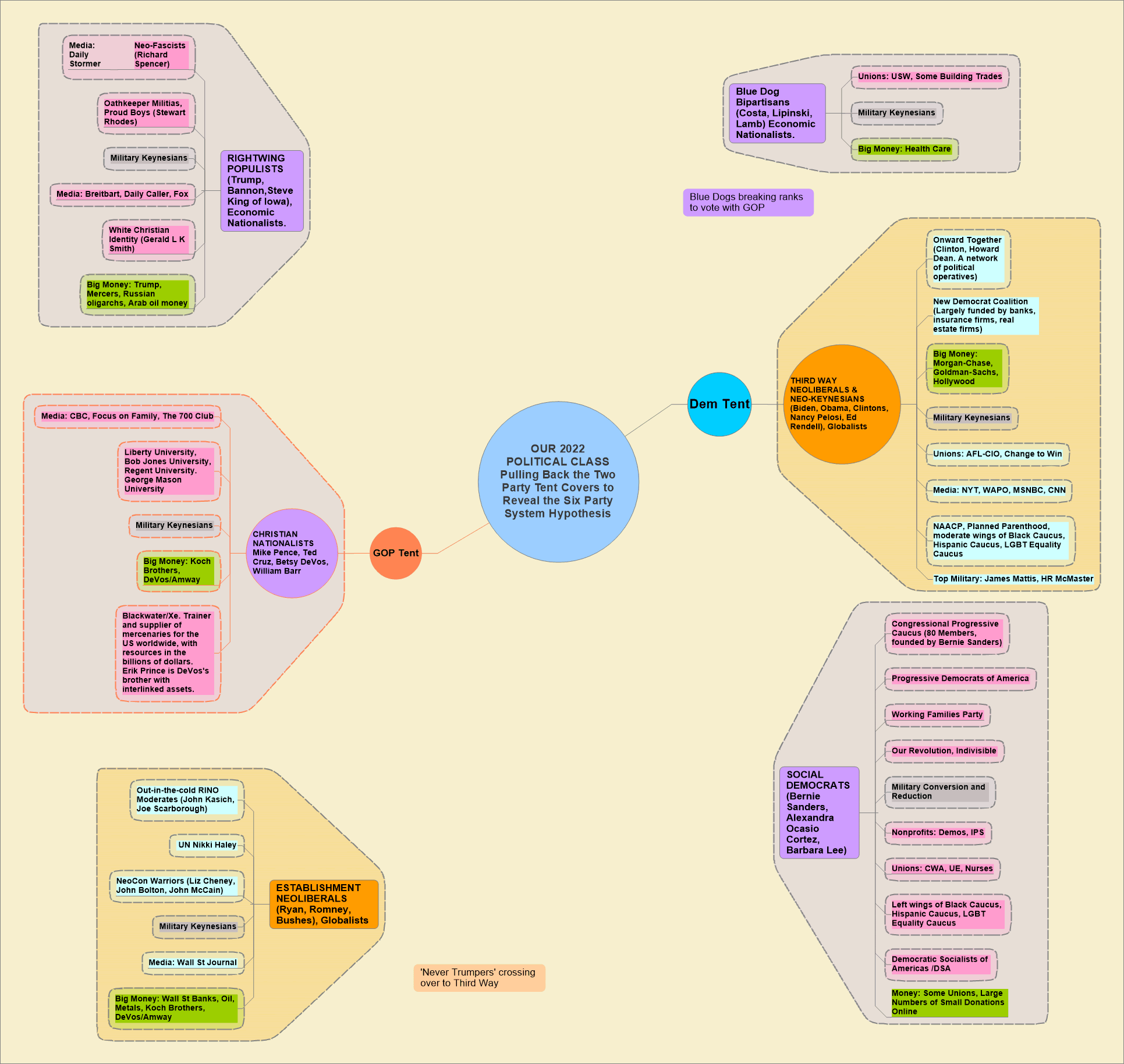

In the earlier versions, I suggested setting aside the traditional ‘two-party system’ frame, which obscures far more than it reveals, and making use of a ‘six-party’ model instead. I suggested that the new hypothesis had far more explanatory power regarding the events unfolding before us. I still like this hypothesis.

Some critics have objected to my use of the term ‘party’ for factional or interest group clusters. The point is taken, but I would also argue that U.S. major parties, in general, are not ideological parties in the European sense. Instead, they are constantly changing coalitions of these clusters with no firm commitment to program or discipline. So I will continue to use ‘parties,’ but with the objection noted. You can substitute ‘factions’ if you like. Or find us a better term.

For the most part, the strategic picture still holds. The ‘six parties’, under two tents, were first labeled as the Tea Party and the Multinationalists under the GOP tent, and the Blue Dogs, the Third Way New Democrats, the Old New Dealers, and the Congressional Progressive Caucus, under the Democratic tent. We had three ‘parties’ under each tent in the second and following versions.

There are still a few minor players outside of either tent—the Green Party campaigns in California, Kshama Sawant’s ongoing battles in the Seattle City Council, the local independent candidates of the Richmond Alliance, and a few more. They might be pretty important in local areas, but still lack the weight to be featured in this analysis.

But let’s move to the central terrain.

First and most essential for us on the left now is Biden’s victory over Trump alongside the persistent clout of Senator Bernie Sanders, who keeps showing far more strength than imagined. Today we would also certainly add the gains made by Alexandra Ocasio Cortez (D-NY) and the growth of ‘the Squad.’ Other progressives wins in Congress and DSA gains in several state legislatures are also noteworthy.

But here’s the danger. Biden’s won by a clear margin, but Trump also gained in total votes over his past numbers. This is dangerous and too close for comfort. Given a 50/50 Senate and a narrow margin in the House, Biden has to govern, as best as he can, alongside the continuing power of Trump and rightwing populism. Moreover, the right includes the full integration of Trump’s forces into the GOP national and state apparatus and Trump’s now overt alliances with growing fascist militias and related groups

Trump’s still refuses to accept his defeat by more than 7 million votes. Acceptance of this ‘Big Steal,’ transformed into a ‘Big Lie,’ is now a loyalty test throughout the Republican party, from top to bottom. Moreover, we all witnessed Trump’s attempted coup on Jan. 6, 2021, complete with an insurrectionary assault on the Capitol. Hundreds are now sitting in jail and their trials are underway. . The number of Oath Keepers and Proud Boys on trial is a case in point. More importantly, the House Committee on Jan. 6 is starting its public hearings, which promises to be a powerful media exposure.

Therefore, what has moved from the margins to the center of political discourse is the question of a clear and present danger of fascism. Far from an ongoing abstract debate, we are now watching its hidden elements come to light every day in the media. We also see the ongoing machinations in the GOP hierarchy and in state legislatures reshaping election laws in their favor. Now, the question is not whether a fascist danger exists, but how to fight and defeat it.

The outcomes for Biden and Trump, then, challenge, narrow, and weaken the old dominant neoliberal hegemony from different directions. For decades, the ruling bloc had spanned both the GOP transnationals and those transnational globalists in the Third Way Democrats. Now neoliberalism is largely exhausted. This is a major change, opening the terrain for new bids for policy dominance. Team Biden is groping for a yet-to-be-fully -defined LBJ 2.0, largely making major investments in physical and social infrastructure, like universal child care or free community college. Weirdly, the GOP claims to stand for nothing, save fealty, Mafia-style, to Trump. Behind that smokescreen are the politics of fascism and a neo-confederacy.

But the GOP still has three parties. Back in 2016, Politico had characterized them this way: “After the Iowa caucuses” the GOP emerged “with three front-runners who are, respectively, a proto-fascist, [Trump] a Christian theocrat [Cruz] and an Ayn Rand neoliberal [Rubio] who wants to privatize all aspects of public life while simultaneously waging war on the poor and working classes.”

So here’s the new snapshot of the range of forces for today (including a graphic map above).

Under the Dem tent, the three main groups remain as the Blue Dogs, the Third Way Centrists and the Rainbow Social Democrats. Although small, the Blue Dogs persist, especially given their partnership with West Virginia’s Joe Manchin in the Senate. With Biden in the White House, the Third Way group keeps and grows its major clout and keeps most of its African American, feminist and labor allies. The Sanders Social Democratic bloc has gained strength, especially with the growing popularity of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the growth of ‘The Squad. ‘Sanders has also formed and kept a progressive-center unity against Trump and has helped define ‘Build Back Better’ and other Biden reform packages.

The changes under the GOP tent have been radical, although keeping its three parties. The ‘Never Trumpers’, despite voting for Biden, have yet to split off entirely. In fact, despite the efforts to purge her, Liz Cheney of Wyoming continues fighting fiercely against Trump and his fascist measures and minions. The Jan. 6 insurrection also brought to the surface the tensions between the Christian nationalists headed by former Vice President Mike Pence and Trump’s rightwing populists. Apart from tactics, a key difference between the two is Koch money and its institutional power. The Koch brothers never liked or trusted Trump, and never funded him directly, pouring their millions into the Christian Nationalist bloc instead.

Trump still has a tight grip on the entire party, but without his White House power, the number of his GOP critics is on the rise. Daily. Trump has denounced all rivals from these two groupings, and is building his alliances with the Jan. 6 insurrectionist supporters in state legislatures. The goal is new anti-voter laws to control those counting the votes and defining the districts in the years ahead.

Let’s now look closer, starting from the left upper corner of the map:

The Rightwing Populists

This ‘party’, as mentioned, has taken over the GOP and is now tightening its grip. Trump was originally an ‘outlier elite’ with his own bankroll but now supplemented with funds from Russian oligarchs and Arab oil fortunes (See ‘Proof of Conspiracy ‘by Seth Abhramson). He is also still directly connected to the Robert Mercer family fortune, the 4th ranking billionaire funding rightwing causes. For example, the Mercers keep Breitbart News afloat and funded the career of Steve Bannon, former Trump ‘strategist’ that took him to victory in the last stretch. Along with Breitbart, Fox News is the main hourly mouthpiece for Trump’s war against the mainstream ‘fake news’ mass media. There are dozens of smaller outfits, but with millons of followers

Trump is also pulling in some new wealth. One example is Julia Jenkins Fancelli, an heiress to the fortune of the popular Publix supermarket chain. Alternet reports others: “One example is Dan and Farris Wilks, two billionaire siblings who have worked in the fracking industry in Texas and have “given a combined $100,000 toward the president’s reelection.” The Wilkes Brothers supported Sen. Ted Cruz over Trump in the 2016 GOP presidential primary but are supporting Trump in 2020.”

But major events reveal some fault lines. The House has now impeached Trump twice, once following the Jan. 6 events and earlier in 2019. The Senate followed up by acquitting him in both cases. In Trump’s second impeachment, 10 GOPers in the House and seven in the Senate votes against him. This is as good of an indictor as any of the remaining small but persistent strength of ‘regular’ Republicans in their own party.

The impeachment efforts, worthy in their own right, were also a major result of Trump’s fierce ongoing political warfare against the ‘Deep State.’ The battle is actually a contest for a new ‘America First’ white nationalist hegemony against the old neoliberal globalists under both tents. The ‘Deep State’ is the federal civil service and includes the ‘Intelligence Community,’ with a long list of Trump-targeted CIA and FBI leaders, supposedly corrupt, of which FBI director James Comey was the first to be purged. The real ‘corruption’ was their refusal to pledge loyalty to Trump personally, again like an old-style Mafia boss.

In the first impeachment vote in Feb. 2020, the sole breakaway vote was Mitt Romney on Article One. Romney, with considerable wealth himself, is also a Mormon bishop, and his LDS church recently listed holdings of over $37 billion with the SEC. This is a factor in Romney’s ability to stand alone. At the moment, however, the much-weakened GOP’s old Establishment is left with the choice of surrender, or crossing over to the Third Way bloc under the Dem tent. A good number already did so to vote for Biden in the Dem 2020 primary and general, expanding the Dem electorate to the right.

Trump now needs even more to shore up an alliance with the Blue Dogs. But it remains tactical, stemming from his appeals to ‘Rust Belt’ Democrats and some unions on trade and tariff issues, plus white identity resentment politics. The economic core of rightwing populism remains anti-global ‘producerism’ vs ‘parasitism’. Employed workers, business owners, real estate developers, small bankers are all ‘producers’. They oppose ‘parasite’ groups above and below, but mainly those below them—the unemployed (Get a Job! as an epithet), the immigrants, poor people of color, Muslims, and ‘the Other’ generally. When they attack those above, the target is usually George Soros, a Jew.

Recall that Trump entered politics by declaring Obama to be an illegal alien and an illegitimate officeholder (a parasite above), but quickly shifted to Mexicans and Muslims and anyone associated with ‘Black Lives Matter.’ This aimed to pull out the fascist and white supremacist groups of the ‘Alt Right’–using Breitbart and worse to widen their circles, bringing them closer to Trump’s core. With these fascists as ready reserves, Trump reached farther into Blue Dog territory, and its better-off workers, retirees, and business owners conflicted with white identity issues—immigration, Islamophobia, misogyny, and more. Today they still largely make up the audience at his mass rallies.

Trump’s outlook is not new. It has deep roots in American history, from the anti-Indian ethnic cleansing of President Andrew Jackson to the nativism of the Know-Nothings, to the nullification theories of Joh C. Calhoun, to the lynch terror of the KKK, to the anti-elitism and segregation of George Wallace and the Dixiecrats. Internationally, Trump combines aggressive jingoism, threats of trade wars, and an isolationist ‘economic nationalism’ aimed at getting others abroad to fight your battles for you. At the same time, your team picks up the loot (‘we should have seized and kept the oil!’).

Trump’s GOP still contains his internal weaknesses: the volatile support of distressed white workers and small producers. At present, they are still forming a key social base. But the problem is that Trump did not implement any substantive programs apart from tax cuts. These mainly benefited the top 10% and created an unstable class contradiction in his operation. Moreover, apart from supporting heavy vaccine research, his inability to deal adequately with the coronavirus emergency– over 900,000 dead—is is still undermining the confidence of some of his base. Most of what Trump has paid out is what WEB Dubois called the ‘psychological wage’ of ‘whiteness’, a dubious status position. Thus white supremacist demagogy and misogyny will also continue to unite a wide array of all nationalities of color and many women and youth against him.

Trump’s religious ignorance, sexual assaults and a porn star scandal always pained his alliance with the Christian Nationalist faction: (Mike Pence, Betsy DeVos, et. al.), and the DeVos family (Amway fortune). They were willing to go along with it for the sake of judicial appointments, with the 5-4 Supreme Court ruling against Black voters in Alabama only one major achievement. The alliance, nonetheless, has become more frayed since Jan. 6 and the ‘Hang Mike Pence’ spectacle. But some stalwarts stood fast. The billionaire donor to the GOP right, Devos’s brother Erik Prince is a case in point. He amassed billions from his Blackwater/Xe firms that train thousands of mercenaries, These forces serve as ‘private contractors’ for U.S. armed intervention anywhere. Prinz is now reportedly preparing to spend a few million sending spies and other disruptors into ‘liberal groups’ to do dirty work in Trump’s favor.

The Christian Nationalists

This ‘party’ grew from a subset of the former Tea Party bloc. It’s made up of several Christian rightist trends developed over decades, which gained more coherence under Vice President Mike Pence. It includes conservative evangelicals seeking to recast a patriarchal and racist John Wayne into a new warrior version of Jesus. It was strengthened for a period by the addition of William Barr as the Attorney General, He brought Opus Dei and the Catholic far-right, a minority with the American Catholic Church, closer to the White house. But seeing that Trump was about to go beyond the law in trying to overturn the 2020 election, Barr jumped ship and resigned just in time

A good number of Christian nationalists, however, are the Protestant theocracy-minded fundamentalists, especially the ‘Dominionist’ sects in which Ted Cruz’s father was active. They present themselves as the only true, ‘values-centered’ (Biblical) conservatives. They argue against any kind of compromise with the globalist ‘liberal-socialist bloc’, which ranges, in their view, from the GOP’s Mitt Romney to Bernie Sanders. They are more akin to classical liberalism than neoliberalism in economic policy. This means abandoning nearly all regulations, much of the safety net, overturning Roe v. Wade, getting rid of marriage equality (in the name of ‘religious liberty’) and abolishing the IRS and any progressive taxation in favor of a single flat tax. Salon in April 2018 reported:

“This rightwing Christian movement is fundamentally anti-democratic. Their ‘prayer warriors’ do not believe that secular laws apply to them, thus making it acceptable, if not honorable, to deceive non-believers in order to do God’s work. Many evangelicals in the Christian nationalist or ‘dominionist’ wing of the movement want the United States to be a theocracy. In some ways, this subset of the evangelical population resembles an American-style Taliban or ISIS, restrained (so far) only by the Constitution.”